|

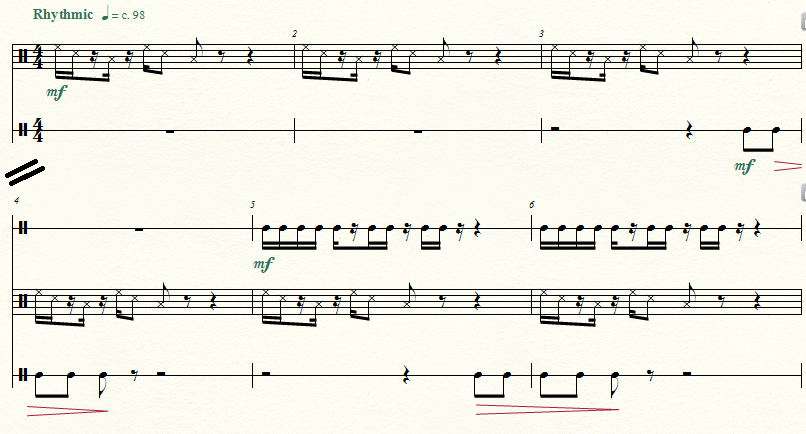

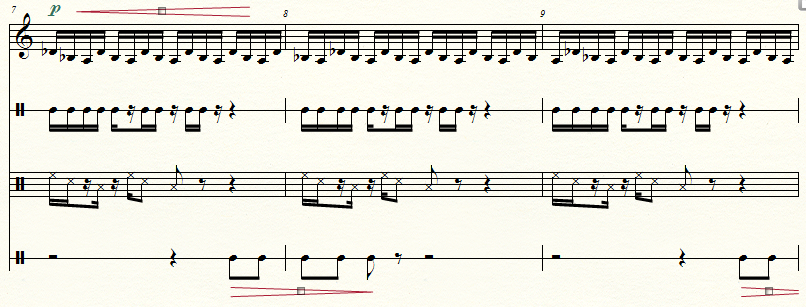

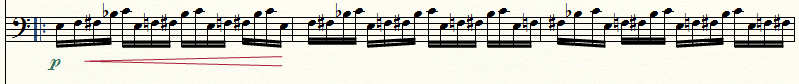

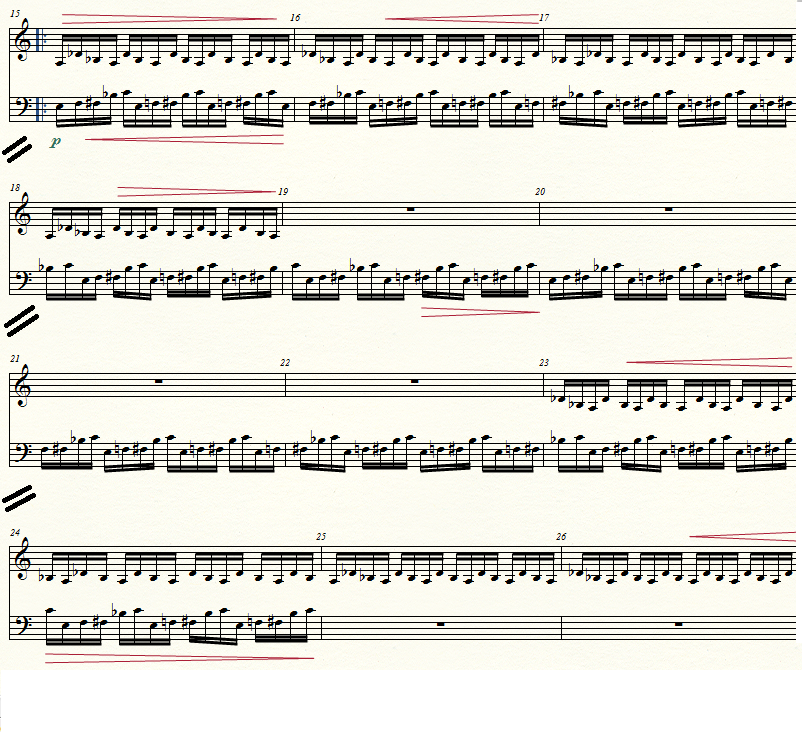

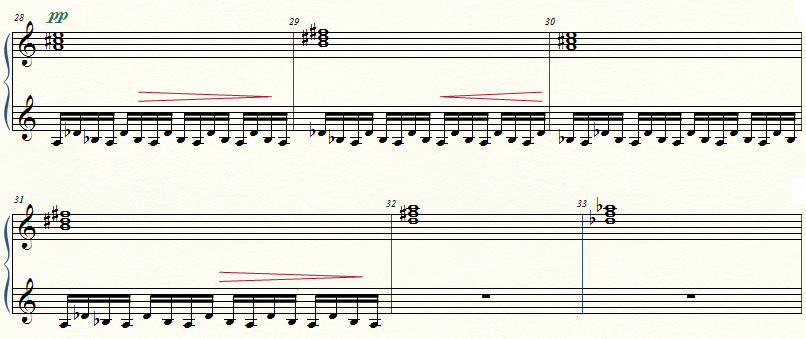

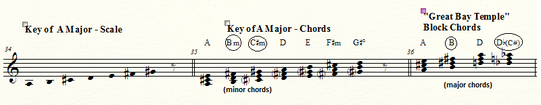

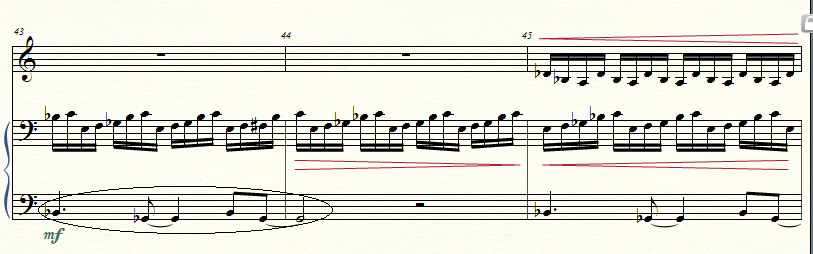

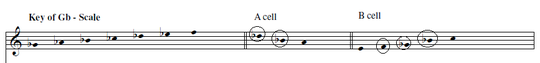

Hello friends! I hope you've put on your thinking caps this week, because this post is going to be down and dirty with some intense music theory. I'm trying to keep this Blog fresh by coming up with different formats for the articles; last week, I picked a musical concept (the counter-melody) and we looked at a few pieces from different games that used it to great effect. This week, I thought I'd try doing a full-fledged theory analysis of just one piece from a video game, and pick apart all of the different musical elements within it. And I've just been DYING to dig into this piece for a while now: the Great Bay Temple theme from Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask. Not exactly music we'll be hearing live in concert anytime soon, eh? :-P This probably is not considered one of the more well-known pieces from Majora's Mask, and the game did not have a ton of new music to begin with. Not that this is a bad thing, but--the soundtrack felt much smaller than its predecessor Ocarina of Time. It wasn't just that they re-used a lot of music from OoT; they also re-used a lot of the same themes within Majora's Mask. Clock Town, the center of Termina and thus where you spend a lot of your time, has the same theme from day to day (rehashed to reflect the weather and circumstances); the cursed areas outside of Clock Town also used the same “Majora's Theme” simply with different instrumentation; and the temples' music was on the reeeeally murky and ambient side—but then again, this entire game was really out of left field for the Zelda franchise. And what a gem it was! I loved the darkness of the story, the strong theme of the meaning of friendship, and the challenge of the side stories and side quests. This game really got you to know the characters in Clock Town, and it certainly was nice to have a break from Ganondorf for once, wasn't it? This game did have some new pieces that really added a lot to the game (i.e. the Song of Healing, the End of the World), but I have always considered the Great Bay Temple theme one of my favorites. Ever since I heard it when I was fourteen, it just stuck with me. I'm always drawn to highly rhythmic pieces with a lot of neat percussive effects in it, and this certainly has elements of that—but at first glance, this does not seem like a piece most people walk around humming after they've played the game, right? But when I finally sat down and started analyzing it this week, I discovered there was a lot and I mean a LOT more to it than meets the eye--or the ear, I should say :-P So! Ever since I started this blog, I've been trying to make these posts as “user-friendly” as possible, so people who are non-musicians, or unfamiliar with music theory can understand and appreciate the elements that go into the composition of a video game piece. But the Great Bay Temple theme is a violently erupting volcano of ingenious musical design, and I thought maybe this would be a good time to just go nuts and dig deep into my nerdy, music theory side. I'm going to explain everything as I go along, so don't be daunted if you're not a trained musician!! This article is just going to cover a lot more info than previous blogs. Now, I haven't met any myself, but if those stereotypically snooty, VGM-scoffing musical theorists really exist, then I sincerely hope they stumble upon this article sometime--I'm sure it would surprise them to see just how much depth and integrity that video game music can possess :) The Level Design A little backstory, for those who are unfamiliar with the game: Great Bay Temple is the token Zelda water temple. Now, the challenge of the Water Temple in the previous game (OoT) was navigating an area in which Link was ill-suited to travel: it was filled with water. Your choice was to either put on the 400-pound boots and walk around really slowly underwater, or do the Unheroic Side-Stroke. It was annoying and difficult. However, in Majora's Mask, Link has just obtained a mask that allows him to turn into a Zora (fish-creature), which means he'll be moving easily and rapidly through the water. The challenge in the Great Bay Temple is that it is designed around a series of water pumps attached to underwater propellers, which change the direction and flow of the water into tunnels leading to different areas of the dungeon—so as tempting as it is to zip around in your Zora costume, you have to be careful not to get sucked into the wrong tunnel. So, in summary, the basic elements of this temple: Speedy travel with the Zora mask. Giant tanks of water. Water pumps, controlled by gears. Propellers moving the water. Rapid currents of water, sometimes in opposing directions. Now listen to the song again. There's a lot of musical imagery to support the environment and design of the temple; let's walk through the piece step by step and figure out how this was done. The Ambience The piece starts out with a simple ambience (atmospheric sound), a machine-like hum. Link is essentially in a giant pumping station, so ambience is obviously a good fit. Then the drum patterns start up. The first drum sound has a hollow ring, as though banging on a large, empty cannister, or oil drum; the second sound reminds me of the crash of heavy machinery, and the third is almost electronic in nature. On a whole, the drum patterns have a very mechanical, factory-like vibe to them; while they are the driving rhythmic force of the piece, I would say that the choice of drum timbres (colors) adds also to the ambience that the composers are going for: inside a machine. Polythematic Composition Then at m.7, we've got our first actual pitches (which I call the “A” theme): Before we go on, let's review the definition of melody, courtesy of Wikipedia: “a linear succession of musical tones which is perceived as a single entity. In its most literal sense, a melody is a combination of pitch and rhythm.” Look at the A passage. Not very striking melodically, is it? In fact, I wouldn't call this a melody at all. What we have here is not a deliberately constructed combination of pitch and rhythm; what we have here is simply 3 notes repeating over and over again. at the same rate of subdivision (in this case, sixteenth notes). To top it all off, the pattern does not divide equally into the time signature. If I rebeamed this passage to reflect the 3-note pattern, it would look like this: Because the pattern doesn't divide evenly, that means each measures has a different pitch of the cell as the downbeat (first beat of the measure). As a result, there is no specific rhythmic importance attached to these notes at all; they just loop continuously. So if this isn't a melody...what is it? In music theory, we would call that group of 3 notes a cell. Wikipedia defines a musical cell as “the smallest indivisible unit of rhythmic and melodic design that cn be isolated, or can make up one part of a thematic context.” What is a theme? Also according to Wikipedia, it is “the material, usually a recognizable melody, upon which part or all of a composition is based.” This passage is certainly recognizable, even if it is not what we would call “melodic.” So, what we have here is a theme, based off of a 3-note cell. BUT WAIT. Going on to m.15, we see another, different theme start up. Let's call this one B; have a listen to just the B theme, isolated: Take a look at the notes; we have another repeating pattern. This one is based off of a 5-note cell, also repeating on a 16th note subdivision. Being a 5-note pattern, it also does not divide evenly into the time signature. What happens when you put the two themes together, as in m.15? MADNESS: Since there are two different themes that make up this piece, we would call this...wait for it...a polythematic composition. Pretty neat effect, right? Not only are the themes played by the same instrument, but they're also in the exact same register; they weave in and out of each other, and since the cells are different lengths (3 and 5), they never line up in any sort of rhythmic way. It's a very cool, watery, murky sound. Harmonic Planing and Implied Keys Now for the last few elements that make up this piece—until now, we've just had ambience, drums, and two conflicting, unrelated themes. We do actually have brief moments of harmony at the end of the piece. In m. 25, everything drops out completely and we're left with just the A theme; then, very faintly, we hear flute-like block chords. The first chord is an A major chord (A, C#, E). Now, since the notes in the A theme do contain C# (Db), and A, my ear automatically tells my brain, “Well, we must be in the key of A major!” But some of those chords do NOT belong in the key of A: In a major key, there are naturally a few minor chords; but all of the chords in the passage are major. How was this achieved? Every note in the chord moves the exact same interval (distance) to the next set of notes. This kind of parallel movement of notes is called harmonic planing, or parallel harmony. What does this do? In this case, it prevents us from hearing a definitive, actual key signature. But before we chalk this one up to a simple case of harmonic planing, check out that last block chord, a Db major chord. Then look at the notes in m. 43--a Bb and Gb, implying a Gb major chord (Gb, Bb, Db) The Db in m.33 is the dominant chord of Gb. Very, VERY simply put, the use of these two chords, in that order, could imply that we are in the key of Gb at m.43. And it's JUST a few measures after this that the entire piece starts looping. Now try THIS on for size: let's look at the seemingly random 3 and 5 note cells for the A and B themes. They seem conflicting at first...but if we look at the pitches in the context of the key of Gb... We are...ALMOST in the key of Gb. Almost...but enough of the pitches in the cells are from outside the scale. As a result, the key of Gb is obscured for the entire piece...until those pitches in the bass at m.43.

So this seemingly arbitrary choice of harmonic planing in mm.28-33 actually could be construed as setting up the key for the ENTIRE PIECE: Gb. The Summary (Here's hoping you're still reading) So! Now that most of you are bored to tears and are trying to remember why you thought it would be fun to read this blog: what does all of this mean musically? We've discussed the piece in the most dry, emotionally-removed music theory terminology available; we know now that there was actually a lot of cool stuff going on throughout the composition. Now let's connect the pieces and see what this music adds to the game.

You know what my favorite part of this piece is? How elegantly simple it is. We have like what, 5-6 different instrument sounds, including the percussion? Two straightforward themes, a moment with harmonizing chords, the simple background ambience? And while the piece was certainly memorable to me, it never distracted me from the gameplay. The music was meant to be a supporting feature, not the main event. And how did Kondo and Minegishi do this? With a brilliant mixture of just a few elements, like the recipe for a cake. I can make an eight-tier wedding cake and recreate the Mona Lisa on it with fifty-seven different shades of icing; or, I can throw some flour, sugar, butter and banana in a bowl and make my grandmother's plain-looking but ridiculously tasty banana cake. You don't always need a lot of bells and whistles to make a really great piece of video game music; the “greatness” of a piece comes from how effective it is in the level, and I think the Great Bay Temple music has certainly done that. What do you think? Enjoy this week's arrangements of the Dungeon/Underworld theme from the original Legend of Zelda, and Great Bay Temple from LoZ: Majora's Mask! More on the way!

12 Comments

|

AuthorVideo game music was what got me composing as a kid, and I learned the basics of composition from transcribing my favorite VGM pieces. These are my thoughts and discoveries about various game compositions as I transcribe and study them. Feel free to comment with your own thoughts/ideas as well! Archives

July 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed