|

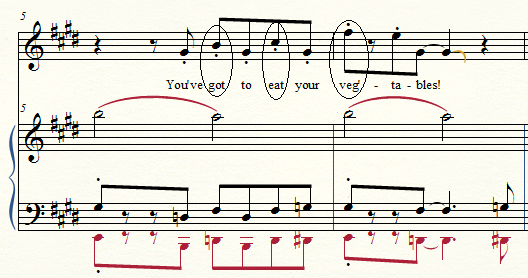

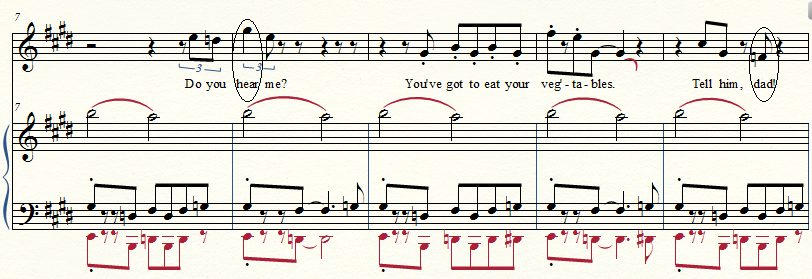

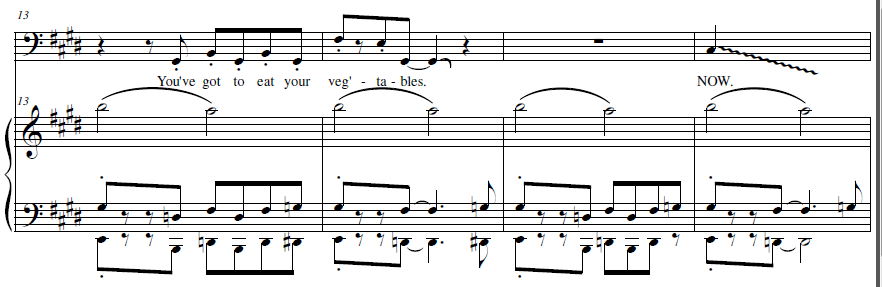

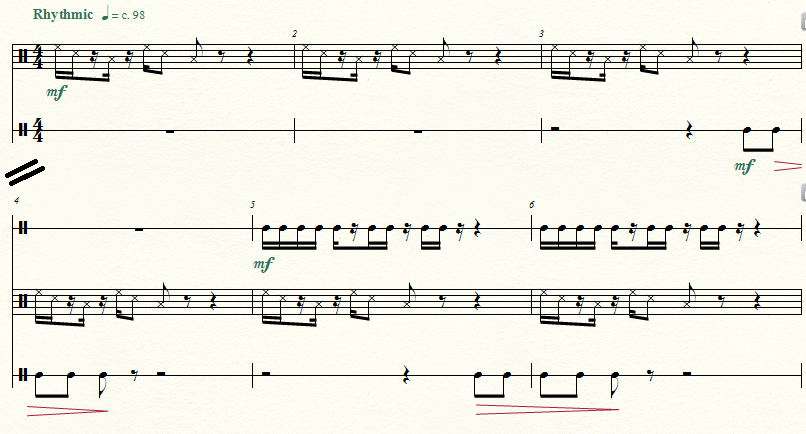

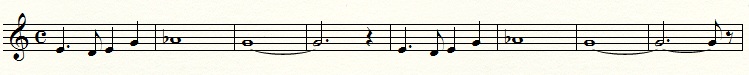

Hello friends! Sorry this post is a bit late--I meant to have this done last week, but last week was pretty brutal! When I'm not on the road with VGL, I work as a singer/pianist for various churches on Long Island. This past week, Catholic churches were celebrating Ash Wednesday, for which I was hired to do four gigs in Queens, Brooklyn and Nassau County. All of them involved playing the organ. It was a terrifying day for two big reasons: 1) I'm only just learning to play the organ over the past month or so, and 2) I had a nasty cold that reached its zenith on that very day. I croaked my way through the masses and managed to play the pedals without falling off the organ bench, so we'll call it a win :-P But the cold took a lot out of me, I didn't get as much writing done this week. So, this is going to be a pretty short post, but hey, maybe that's a good thing after the NOVEL I wrote last week :-P So, last Tuesday night, I was coughing up a lung and couldn't get to sleep because of my screaming sore throat. Like the hopeless geek I am, I decide that to help me sleep, I'll pick out some video game music and transcribe until my brain goes into a cold shutdown and I pass out. As I booted my computer, I immediately thought of the old DOS games I used to play when I was in elementary school. My sister and I were DOS addicts, we loved all of those old games—Word Rescue, Math Rescue, Monster Bash, God of Thunder, Lemmings, and of course, Commander Keen. He was definitely one of my favorites! I loved the silly story, fun gameplay, the catchy music, the Dopefish. How can you not love a game that has a creature called “the Dopefish?” He was the terror of the deeps, and to this day, I don't believe I have ever beaten Dopefish level. So, I started Youtubing the music. I was pleasantly surprised to discover that the songs actually had titles, instead of just “Level 1, Level 2” etc. One of the Youtube videos was called “You've Got to Eat Your Vegetables.” I clicked it, and laughed when I recognized the tune—it happened to be the music that accompanies the Dopefish level. Then I gaped at the Youtube video description. An interview with Bobby Prince in the 90s revealed that this wasn't originally a piece of instrumental music; it was a song. WITH WORDS. THE DOPEFISH THEME...HAD WORDS...*EXPLODE* Apparently, Bobby Prince, the God of Music at iD software, had written this piece to accompany a completely different installation of the Commander Keen series. The game was supposed to begin with a cutscene of Billy Blaze at the dining room table, refusing to eat his vegetables. I'm just guessing from what Bobby describes in the interview, but it seems that this song was meant to “vocalize” the words, which I'm guessing would just appear as text at the bottom of the screen. I say “vocalize” because I'm assuming no one was actually going to sing the lyrics; the gamer was most likely going to read the text while hearing the melody, and his/her brain would automatically link the two together. But Prince didn't just write a random melody and slap some words on it; he reflected the inflection (speech pattern) of the characters' voices through the contour, or "shape," of the melody. All melodies have a shape of some sort, but it is more important than ever when you're setting words to music. The English language has a natural rhythm to it; our voices rise and fall when we talk because some words in a sentence are more important than others. So, when writing a melody to go with lyrics, composers have to keep that natural word stress in mind, to make sure that they aren't musically stressing the wrong words. And Prince does this perfectly! Take the very first line of the son. Billy's mother is the first one to yell at him; what would an exasperated mother sound like if she was telling you to eat your vegetables? She wouldn't just say "Billy, you've got to eat your vegetables" in a monotone; it would be something like, “BILLy! You've GOT to EAT your VEGetables!” There are certain words and syllables in that sentence that are stressed, right? Now listen to the melody line. He stressed those words and syllables in the melody line by placing them on higher notes--the rise and fall of her voice is exactly reflected in the rise and fall of the melody-line. Then she says, “do you hear me?! You've got to EAT your VEGETABLES!" Appealing to her husband, "Tell him, Dad...” Prince expresses the exasperation in her voice through that random F-natural on "Dad." Then here comes Dad, with the same exact melody—only now the melody-line is taken down two octaves, to reflect a man's lower voice. He says, “You've got to eat your vegetables. NOW.” Check out that glissando—great way to express the command in his voice as he says “NOOOWWW!” Lastly, here comes Billy's little sister, teasing him at the table. Now the melody-line has been taken up two octaves, to reflect a little girl's voice. And we have the classic teasing sound; Prince adds those extra halfsteps to it to make it sound a little more grating: How cool is that? Without any spoken/sung words at all, the contour of the melody conveys EXACTLY what Billy's family sounds like when they speak to him; exasperated mom, fed-up dad, and giggling little sister. And then you have the supporting accompaniment itself; the tempo is deliberately slow and draggy, the instrument sounds are heavy and clunky--all of this clearly represents Billy's boredom and complete lack of will to eat his vegetables. And nobody even said a word. Hail to the Prince, baby!

Enjoy this week's transcriptions for You've Got to Eat Your Vegetables and Map Theme from Commander Keen 4, and Laboratory from Bio Menace! More on the way!

7 Comments

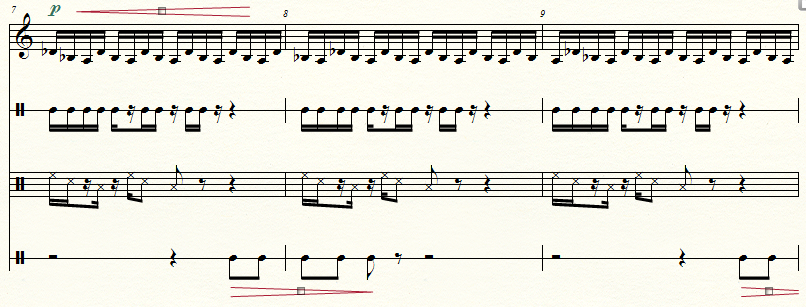

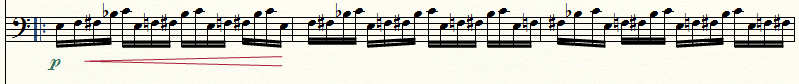

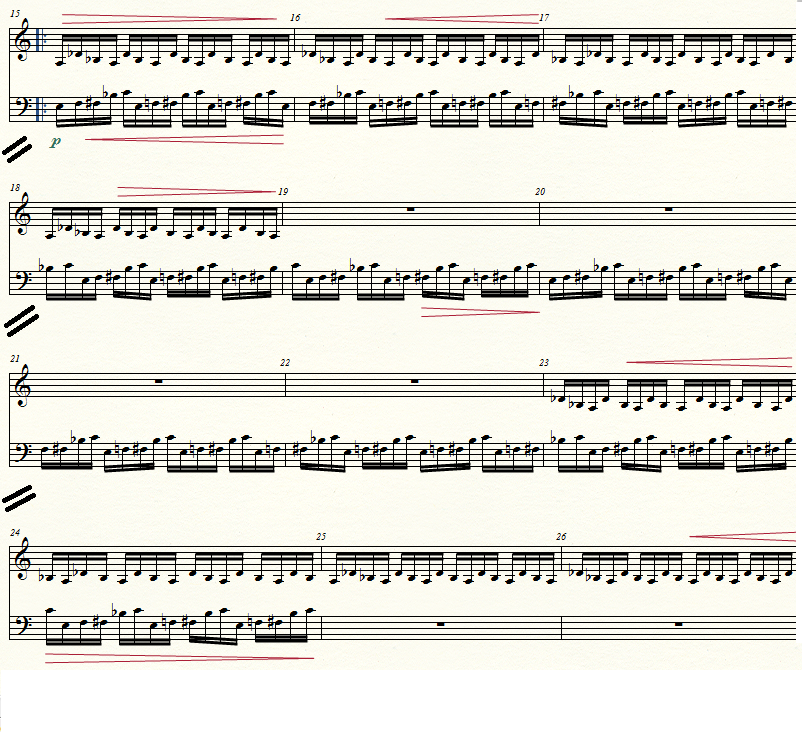

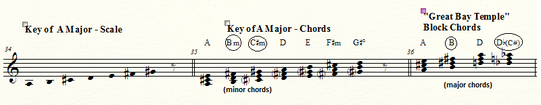

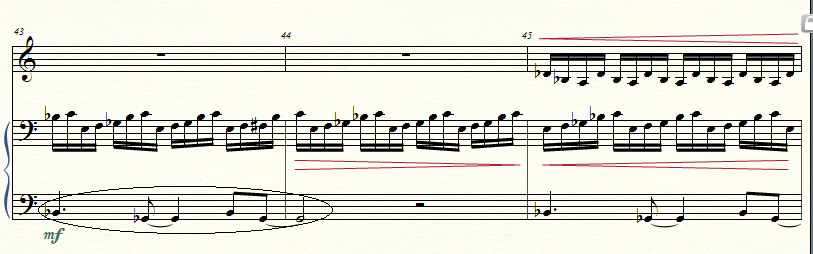

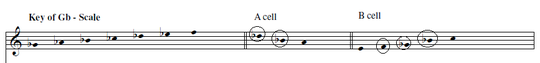

Hello friends! I hope you've put on your thinking caps this week, because this post is going to be down and dirty with some intense music theory. I'm trying to keep this Blog fresh by coming up with different formats for the articles; last week, I picked a musical concept (the counter-melody) and we looked at a few pieces from different games that used it to great effect. This week, I thought I'd try doing a full-fledged theory analysis of just one piece from a video game, and pick apart all of the different musical elements within it. And I've just been DYING to dig into this piece for a while now: the Great Bay Temple theme from Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask. Not exactly music we'll be hearing live in concert anytime soon, eh? :-P This probably is not considered one of the more well-known pieces from Majora's Mask, and the game did not have a ton of new music to begin with. Not that this is a bad thing, but--the soundtrack felt much smaller than its predecessor Ocarina of Time. It wasn't just that they re-used a lot of music from OoT; they also re-used a lot of the same themes within Majora's Mask. Clock Town, the center of Termina and thus where you spend a lot of your time, has the same theme from day to day (rehashed to reflect the weather and circumstances); the cursed areas outside of Clock Town also used the same “Majora's Theme” simply with different instrumentation; and the temples' music was on the reeeeally murky and ambient side—but then again, this entire game was really out of left field for the Zelda franchise. And what a gem it was! I loved the darkness of the story, the strong theme of the meaning of friendship, and the challenge of the side stories and side quests. This game really got you to know the characters in Clock Town, and it certainly was nice to have a break from Ganondorf for once, wasn't it? This game did have some new pieces that really added a lot to the game (i.e. the Song of Healing, the End of the World), but I have always considered the Great Bay Temple theme one of my favorites. Ever since I heard it when I was fourteen, it just stuck with me. I'm always drawn to highly rhythmic pieces with a lot of neat percussive effects in it, and this certainly has elements of that—but at first glance, this does not seem like a piece most people walk around humming after they've played the game, right? But when I finally sat down and started analyzing it this week, I discovered there was a lot and I mean a LOT more to it than meets the eye--or the ear, I should say :-P So! Ever since I started this blog, I've been trying to make these posts as “user-friendly” as possible, so people who are non-musicians, or unfamiliar with music theory can understand and appreciate the elements that go into the composition of a video game piece. But the Great Bay Temple theme is a violently erupting volcano of ingenious musical design, and I thought maybe this would be a good time to just go nuts and dig deep into my nerdy, music theory side. I'm going to explain everything as I go along, so don't be daunted if you're not a trained musician!! This article is just going to cover a lot more info than previous blogs. Now, I haven't met any myself, but if those stereotypically snooty, VGM-scoffing musical theorists really exist, then I sincerely hope they stumble upon this article sometime--I'm sure it would surprise them to see just how much depth and integrity that video game music can possess :) The Level Design A little backstory, for those who are unfamiliar with the game: Great Bay Temple is the token Zelda water temple. Now, the challenge of the Water Temple in the previous game (OoT) was navigating an area in which Link was ill-suited to travel: it was filled with water. Your choice was to either put on the 400-pound boots and walk around really slowly underwater, or do the Unheroic Side-Stroke. It was annoying and difficult. However, in Majora's Mask, Link has just obtained a mask that allows him to turn into a Zora (fish-creature), which means he'll be moving easily and rapidly through the water. The challenge in the Great Bay Temple is that it is designed around a series of water pumps attached to underwater propellers, which change the direction and flow of the water into tunnels leading to different areas of the dungeon—so as tempting as it is to zip around in your Zora costume, you have to be careful not to get sucked into the wrong tunnel. So, in summary, the basic elements of this temple: Speedy travel with the Zora mask. Giant tanks of water. Water pumps, controlled by gears. Propellers moving the water. Rapid currents of water, sometimes in opposing directions. Now listen to the song again. There's a lot of musical imagery to support the environment and design of the temple; let's walk through the piece step by step and figure out how this was done. The Ambience The piece starts out with a simple ambience (atmospheric sound), a machine-like hum. Link is essentially in a giant pumping station, so ambience is obviously a good fit. Then the drum patterns start up. The first drum sound has a hollow ring, as though banging on a large, empty cannister, or oil drum; the second sound reminds me of the crash of heavy machinery, and the third is almost electronic in nature. On a whole, the drum patterns have a very mechanical, factory-like vibe to them; while they are the driving rhythmic force of the piece, I would say that the choice of drum timbres (colors) adds also to the ambience that the composers are going for: inside a machine. Polythematic Composition Then at m.7, we've got our first actual pitches (which I call the “A” theme): Before we go on, let's review the definition of melody, courtesy of Wikipedia: “a linear succession of musical tones which is perceived as a single entity. In its most literal sense, a melody is a combination of pitch and rhythm.” Look at the A passage. Not very striking melodically, is it? In fact, I wouldn't call this a melody at all. What we have here is not a deliberately constructed combination of pitch and rhythm; what we have here is simply 3 notes repeating over and over again. at the same rate of subdivision (in this case, sixteenth notes). To top it all off, the pattern does not divide equally into the time signature. If I rebeamed this passage to reflect the 3-note pattern, it would look like this: Because the pattern doesn't divide evenly, that means each measures has a different pitch of the cell as the downbeat (first beat of the measure). As a result, there is no specific rhythmic importance attached to these notes at all; they just loop continuously. So if this isn't a melody...what is it? In music theory, we would call that group of 3 notes a cell. Wikipedia defines a musical cell as “the smallest indivisible unit of rhythmic and melodic design that cn be isolated, or can make up one part of a thematic context.” What is a theme? Also according to Wikipedia, it is “the material, usually a recognizable melody, upon which part or all of a composition is based.” This passage is certainly recognizable, even if it is not what we would call “melodic.” So, what we have here is a theme, based off of a 3-note cell. BUT WAIT. Going on to m.15, we see another, different theme start up. Let's call this one B; have a listen to just the B theme, isolated: Take a look at the notes; we have another repeating pattern. This one is based off of a 5-note cell, also repeating on a 16th note subdivision. Being a 5-note pattern, it also does not divide evenly into the time signature. What happens when you put the two themes together, as in m.15? MADNESS: Since there are two different themes that make up this piece, we would call this...wait for it...a polythematic composition. Pretty neat effect, right? Not only are the themes played by the same instrument, but they're also in the exact same register; they weave in and out of each other, and since the cells are different lengths (3 and 5), they never line up in any sort of rhythmic way. It's a very cool, watery, murky sound. Harmonic Planing and Implied Keys Now for the last few elements that make up this piece—until now, we've just had ambience, drums, and two conflicting, unrelated themes. We do actually have brief moments of harmony at the end of the piece. In m. 25, everything drops out completely and we're left with just the A theme; then, very faintly, we hear flute-like block chords. The first chord is an A major chord (A, C#, E). Now, since the notes in the A theme do contain C# (Db), and A, my ear automatically tells my brain, “Well, we must be in the key of A major!” But some of those chords do NOT belong in the key of A: In a major key, there are naturally a few minor chords; but all of the chords in the passage are major. How was this achieved? Every note in the chord moves the exact same interval (distance) to the next set of notes. This kind of parallel movement of notes is called harmonic planing, or parallel harmony. What does this do? In this case, it prevents us from hearing a definitive, actual key signature. But before we chalk this one up to a simple case of harmonic planing, check out that last block chord, a Db major chord. Then look at the notes in m. 43--a Bb and Gb, implying a Gb major chord (Gb, Bb, Db) The Db in m.33 is the dominant chord of Gb. Very, VERY simply put, the use of these two chords, in that order, could imply that we are in the key of Gb at m.43. And it's JUST a few measures after this that the entire piece starts looping. Now try THIS on for size: let's look at the seemingly random 3 and 5 note cells for the A and B themes. They seem conflicting at first...but if we look at the pitches in the context of the key of Gb... We are...ALMOST in the key of Gb. Almost...but enough of the pitches in the cells are from outside the scale. As a result, the key of Gb is obscured for the entire piece...until those pitches in the bass at m.43.

So this seemingly arbitrary choice of harmonic planing in mm.28-33 actually could be construed as setting up the key for the ENTIRE PIECE: Gb. The Summary (Here's hoping you're still reading) So! Now that most of you are bored to tears and are trying to remember why you thought it would be fun to read this blog: what does all of this mean musically? We've discussed the piece in the most dry, emotionally-removed music theory terminology available; we know now that there was actually a lot of cool stuff going on throughout the composition. Now let's connect the pieces and see what this music adds to the game.

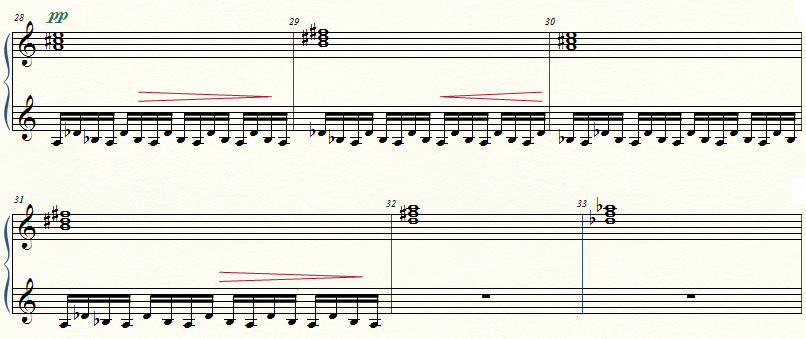

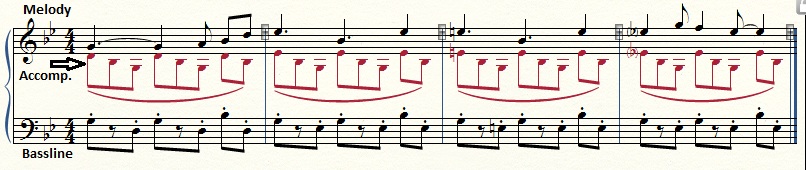

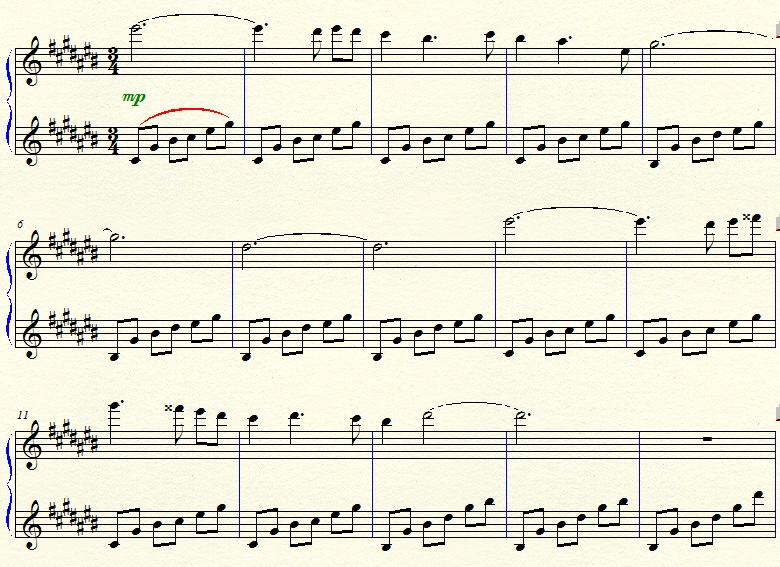

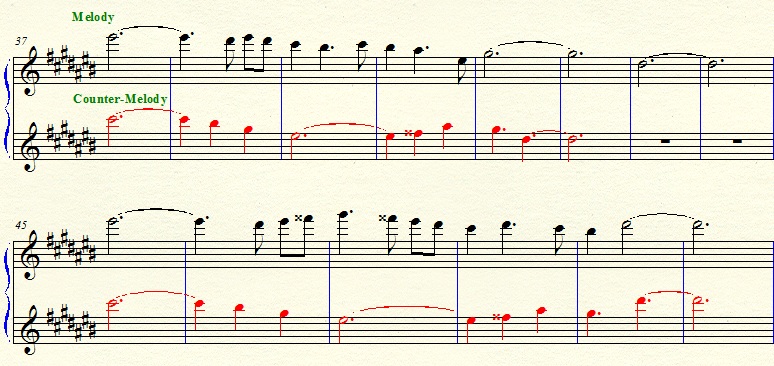

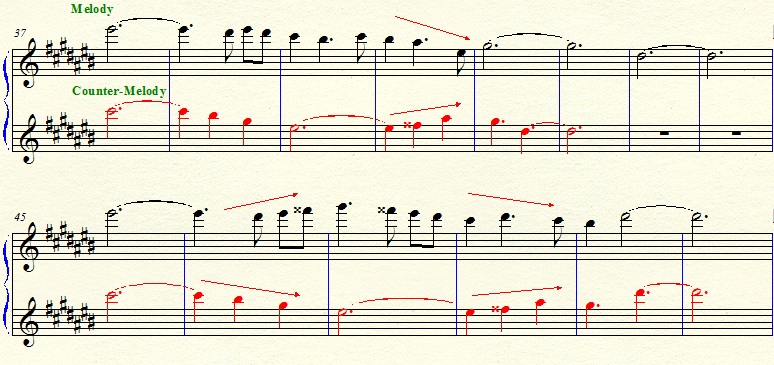

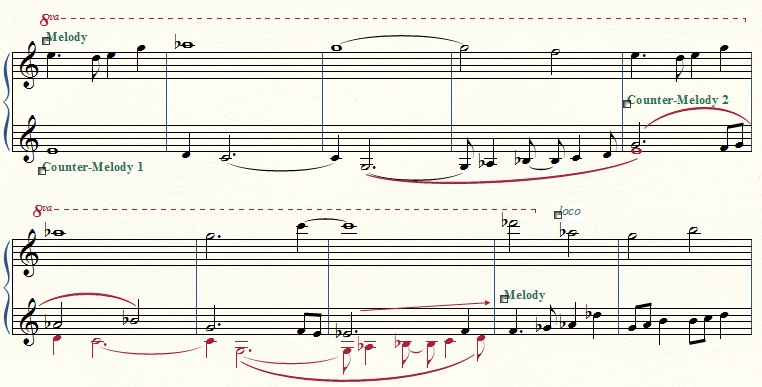

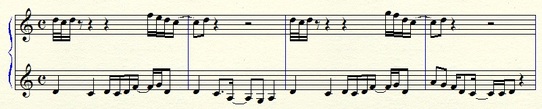

You know what my favorite part of this piece is? How elegantly simple it is. We have like what, 5-6 different instrument sounds, including the percussion? Two straightforward themes, a moment with harmonizing chords, the simple background ambience? And while the piece was certainly memorable to me, it never distracted me from the gameplay. The music was meant to be a supporting feature, not the main event. And how did Kondo and Minegishi do this? With a brilliant mixture of just a few elements, like the recipe for a cake. I can make an eight-tier wedding cake and recreate the Mona Lisa on it with fifty-seven different shades of icing; or, I can throw some flour, sugar, butter and banana in a bowl and make my grandmother's plain-looking but ridiculously tasty banana cake. You don't always need a lot of bells and whistles to make a really great piece of video game music; the “greatness” of a piece comes from how effective it is in the level, and I think the Great Bay Temple music has certainly done that. What do you think? Enjoy this week's arrangements of the Dungeon/Underworld theme from the original Legend of Zelda, and Great Bay Temple from LoZ: Majora's Mask! More on the way! Let's change things up a little! Instead of talking about one game in particular this week, let's talk about a musical concept and how it is applied in games from different series. This is a big post I had a lot of fun writing about, because it's a really neat concept that can be really powerful when used correctly: the counter-melody. Wikipedia says the definition of counter-melody is “a sequence of notes, perceived as a melody, written to be simultaneously with a more prominent lead. Typically a counter-melody performs a subordinate role, and is heard in a texture consisting of a melody plus accompaniment.” What does all of that mean? Basically, a counter-melody is exactly what it sounds like: it's a secondary melody that is meant to “counter” the primary melody. It generally follows a totally different rhythm and contour (shape) than the primary melody, so that it stands out in the texture. A lot of the classic game tunes feature a “melody & accompaniment” form, like in Zelda II's “Palace Theme.” The middle line of music is obviously supporting the melody; it is not a melody in and of itself, but simply an accompanying pattern that lies underneath the melody. A counter-melody is different in that it would also have a melodic character of its own. The strength of using a counter-melody in video game music is that it adds variation to a repeated melody. Let's face it, most video game music HAS to be able to loop endlessly, right? A counter-melody is a great way to prevent the theme from getting old. A counter-melody can make the original melody sound way more interesting, by highlighting the differences between the two. Before we look at Banjo-Tooie's “Atlantis,” one of this week's new transcriptions, let's bounce back to a piece I posted a while ago, “The Bunnies” from Super Mario Galaxy. This is a freaking PERFECT EXAMPLE of how counter-melody works, and in a really lovely, mystical way. First, take a look at about half of the primary melody of The Bunnies. Check out the bottom staff in the piano; obviously just accompaniment, right? We wouldn't describe that figure as being melodic in nature—the repeated pattern is actually closer to an ostinato. Now let's jump ahead in the piece: Check out that second line. It's not simply arpeggiating chords, it has a distinctive shape and character of its own, completely unrelated to the primary melody. The primary melody is much more rhythmically active, on a punctuated harp string sound; the secondary melody has a fuller, sustained sound and less rhythmic activity. Each melody tends to move in opposition to the other; i.e., when one goes up, the other goes down. Now what does this mean musically? What does this convey to the listener? Here's my take on it, my own opinion: The primary melody kind of hops around innocently on that high harp sound, so for me, it represents the bunnies. The secondary melody sounds a bit softer to my ears, and is much more sustained and has a —for lack of a better word--”sci-fi” kind of synthy sound. This is just my own take, but it gives the piece a feeling of weightlessness for me (weightlessness...loss of gravity...HEY WAIT WE'RE IN SPACE). The sound design in and of itself suggests a feeling of wonderment to me, like a child exploring a new world. In the game, Mario has just woken up on a strange planet after being blown into space by Bowser; he wakes up and encounters space bunnies who encourage him to catch them. The purpose of this scene is to give the player more practice with Mario's game controls; so, not only does the music convey the dramatic content of the scene (“Where am I and who are these bunnies?”), it also reflects what is happening for the player him/herself: exploring the controls and the new space world you find yourself in. It's an innocent song, which conveys to the player that he/she can freely experiment with the controls without fear for Mario's life. It's pretty cool how much a simple counter-melody can add, isn't it? Let's look at some more examples. First, “Atlantis” from Banjo-Tooie. Primary melody: Now let's jump ahead to where the counter-melody comes in. Oooooh, something neat is going on here! The melody is obviously in the high flute, and in the lower flute at m. ___ we have what sounds to me like a long, sustained counter-melody. Then, at m. 39, ANOTHER counter-melody splits off of the first one. It only lasts for a few measures until m. 9 of this example, where it takes over the primary melody-line. Now the high flute has a supporting role, the low flute is the primary. It all happens in the span of just a few seconds and the result is seamless, each melody-line weaving in and out of the other (Like fish swimming in the ocean, OH SNAP!) One more example! This is from a personal favorite tune of mine, “Forest Frenzy” from Donkey Kong Country. Take a listen to the entire song here, see if you can pick out the counter-melody just by listening. Hopefully you caught it on that first hearing! Now check it out in the sheet music: Now, for me, the counter-melody does not stick out as strongly in this piece as in the other examples. This piece has a LOT of ostinati in it—those repeating rhythmic and chordal figures make up a lot of the catchiness of the song—but as a result of the repetitive nature of the texture, the counter-melody is kind of lost. It isn't as different from the melody as it could be. In fact, it's almost tempting to call it simply some sort of accompanimental figure—but the fact that it is a single-line melody (one note at a time) and it's in a higher register than the primary melody makes me think that this was intended to be a counter-melody. Not as prominent as the other examples we looked at...but maybe that was the point. This piece is highly rhythmic and the melody is not necessarily the most important feature. So the weaker counter-melody doesn't really take away from the piece, but helps the melody blend in with the rest of the texture.

That's a lot of information to digest, but hopefully you get the idea of all the different ways a counter-melody can function. To finish this ginormous post off, I want to quote a very famous poem by William Carlos William. “It is a principle of music / to repeat the theme. Repeat / and repeat again, / as the pace mounts.” This is more true than ever in video game music, a medium that requires musical looping for the player to have freedom to play at his/her own pace. It is how composers vary the theme, to make it different each time we hear it, that enables us as listeners to not become bored with the same thing over and over again. The video game world has a history steeped in extremely strong melodies—melodies so catchy that you can hear it literally a thousand times and not get bored—but as the hardware grew, so did the capabilities of the composers to create music with more variation. I mean, what was the average length of the typical video game song in the 80's, like one or two minutes? Now we have composers creating much longer pieces with more depth in the music that supports the melody; and that's how we get pieces with beautiful use of counter-melody like “The Bunnies,” “Atlantis” and countless other examples in video game music. Here are some more pieces of video game music with counter-melody...can you spot those moments just by listening? Can you find more examples in video game music that I haven't listed here? I'd love to hear them! New Super Mario Bros. Wii - Staff Roll Legend of Zelda: Windwaker - Staff Roll Ar-tonelico - Singing Hill Star Fox - Main Titles Enjoy this week's transcriptions of Atlantis and Grunty Industries from Banjo-Tooie! More on the way! |

AuthorVideo game music was what got me composing as a kid, and I learned the basics of composition from transcribing my favorite VGM pieces. These are my thoughts and discoveries about various game compositions as I transcribe and study them. Feel free to comment with your own thoughts/ideas as well! Archives

July 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed