|

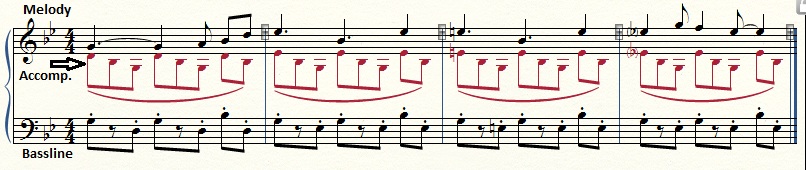

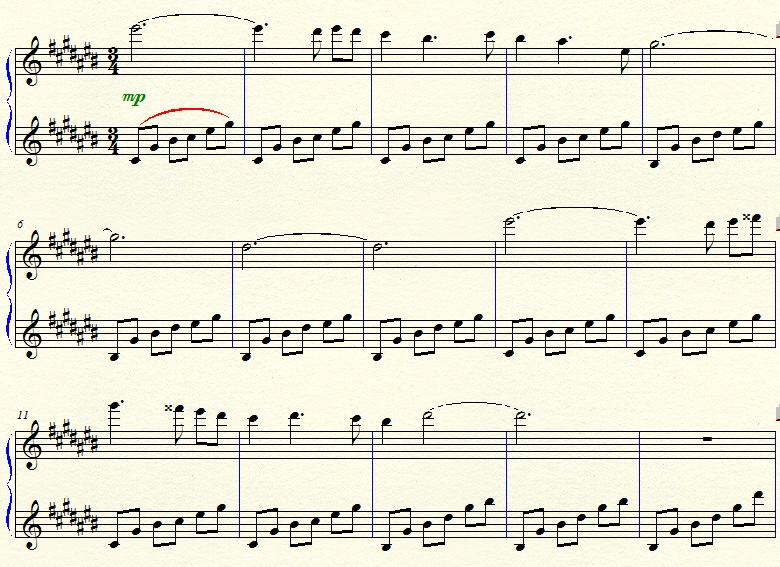

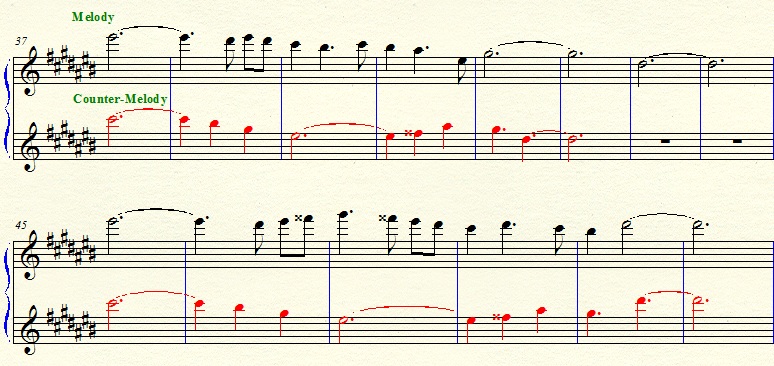

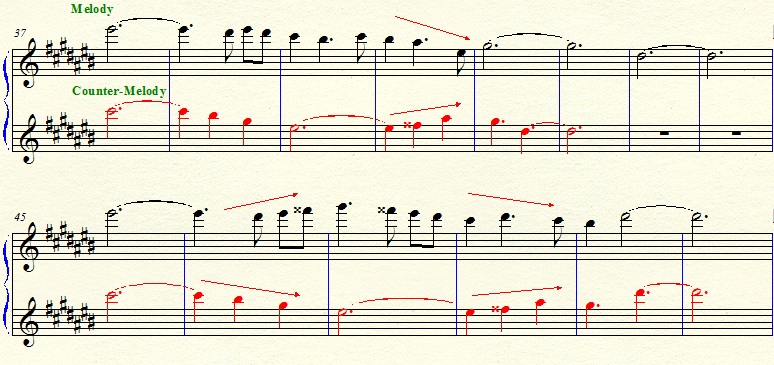

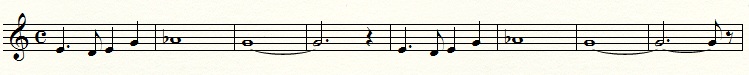

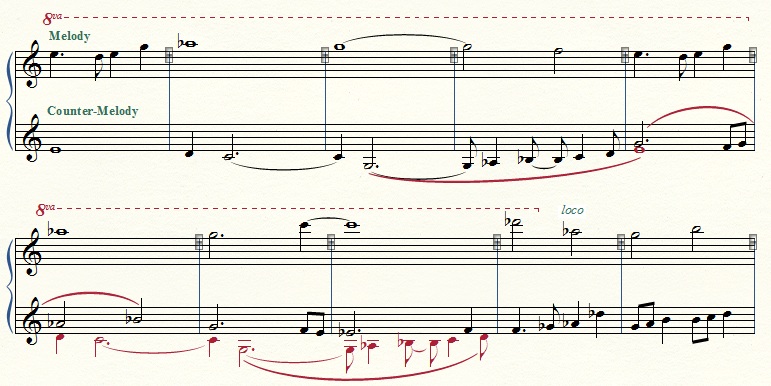

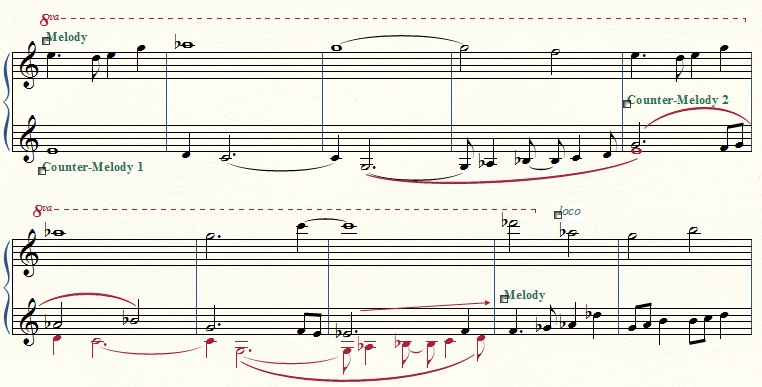

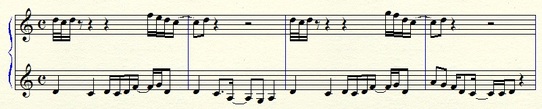

Let's change things up a little! Instead of talking about one game in particular this week, let's talk about a musical concept and how it is applied in games from different series. This is a big post I had a lot of fun writing about, because it's a really neat concept that can be really powerful when used correctly: the counter-melody. Wikipedia says the definition of counter-melody is “a sequence of notes, perceived as a melody, written to be simultaneously with a more prominent lead. Typically a counter-melody performs a subordinate role, and is heard in a texture consisting of a melody plus accompaniment.” What does all of that mean? Basically, a counter-melody is exactly what it sounds like: it's a secondary melody that is meant to “counter” the primary melody. It generally follows a totally different rhythm and contour (shape) than the primary melody, so that it stands out in the texture. A lot of the classic game tunes feature a “melody & accompaniment” form, like in Zelda II's “Palace Theme.” The middle line of music is obviously supporting the melody; it is not a melody in and of itself, but simply an accompanying pattern that lies underneath the melody. A counter-melody is different in that it would also have a melodic character of its own. The strength of using a counter-melody in video game music is that it adds variation to a repeated melody. Let's face it, most video game music HAS to be able to loop endlessly, right? A counter-melody is a great way to prevent the theme from getting old. A counter-melody can make the original melody sound way more interesting, by highlighting the differences between the two. Before we look at Banjo-Tooie's “Atlantis,” one of this week's new transcriptions, let's bounce back to a piece I posted a while ago, “The Bunnies” from Super Mario Galaxy. This is a freaking PERFECT EXAMPLE of how counter-melody works, and in a really lovely, mystical way. First, take a look at about half of the primary melody of The Bunnies. Check out the bottom staff in the piano; obviously just accompaniment, right? We wouldn't describe that figure as being melodic in nature—the repeated pattern is actually closer to an ostinato. Now let's jump ahead in the piece: Check out that second line. It's not simply arpeggiating chords, it has a distinctive shape and character of its own, completely unrelated to the primary melody. The primary melody is much more rhythmically active, on a punctuated harp string sound; the secondary melody has a fuller, sustained sound and less rhythmic activity. Each melody tends to move in opposition to the other; i.e., when one goes up, the other goes down. Now what does this mean musically? What does this convey to the listener? Here's my take on it, my own opinion: The primary melody kind of hops around innocently on that high harp sound, so for me, it represents the bunnies. The secondary melody sounds a bit softer to my ears, and is much more sustained and has a —for lack of a better word--”sci-fi” kind of synthy sound. This is just my own take, but it gives the piece a feeling of weightlessness for me (weightlessness...loss of gravity...HEY WAIT WE'RE IN SPACE). The sound design in and of itself suggests a feeling of wonderment to me, like a child exploring a new world. In the game, Mario has just woken up on a strange planet after being blown into space by Bowser; he wakes up and encounters space bunnies who encourage him to catch them. The purpose of this scene is to give the player more practice with Mario's game controls; so, not only does the music convey the dramatic content of the scene (“Where am I and who are these bunnies?”), it also reflects what is happening for the player him/herself: exploring the controls and the new space world you find yourself in. It's an innocent song, which conveys to the player that he/she can freely experiment with the controls without fear for Mario's life. It's pretty cool how much a simple counter-melody can add, isn't it? Let's look at some more examples. First, “Atlantis” from Banjo-Tooie. Primary melody: Now let's jump ahead to where the counter-melody comes in. Oooooh, something neat is going on here! The melody is obviously in the high flute, and in the lower flute at m. ___ we have what sounds to me like a long, sustained counter-melody. Then, at m. 39, ANOTHER counter-melody splits off of the first one. It only lasts for a few measures until m. 9 of this example, where it takes over the primary melody-line. Now the high flute has a supporting role, the low flute is the primary. It all happens in the span of just a few seconds and the result is seamless, each melody-line weaving in and out of the other (Like fish swimming in the ocean, OH SNAP!) One more example! This is from a personal favorite tune of mine, “Forest Frenzy” from Donkey Kong Country. Take a listen to the entire song here, see if you can pick out the counter-melody just by listening. Hopefully you caught it on that first hearing! Now check it out in the sheet music: Now, for me, the counter-melody does not stick out as strongly in this piece as in the other examples. This piece has a LOT of ostinati in it—those repeating rhythmic and chordal figures make up a lot of the catchiness of the song—but as a result of the repetitive nature of the texture, the counter-melody is kind of lost. It isn't as different from the melody as it could be. In fact, it's almost tempting to call it simply some sort of accompanimental figure—but the fact that it is a single-line melody (one note at a time) and it's in a higher register than the primary melody makes me think that this was intended to be a counter-melody. Not as prominent as the other examples we looked at...but maybe that was the point. This piece is highly rhythmic and the melody is not necessarily the most important feature. So the weaker counter-melody doesn't really take away from the piece, but helps the melody blend in with the rest of the texture.

That's a lot of information to digest, but hopefully you get the idea of all the different ways a counter-melody can function. To finish this ginormous post off, I want to quote a very famous poem by William Carlos William. “It is a principle of music / to repeat the theme. Repeat / and repeat again, / as the pace mounts.” This is more true than ever in video game music, a medium that requires musical looping for the player to have freedom to play at his/her own pace. It is how composers vary the theme, to make it different each time we hear it, that enables us as listeners to not become bored with the same thing over and over again. The video game world has a history steeped in extremely strong melodies—melodies so catchy that you can hear it literally a thousand times and not get bored—but as the hardware grew, so did the capabilities of the composers to create music with more variation. I mean, what was the average length of the typical video game song in the 80's, like one or two minutes? Now we have composers creating much longer pieces with more depth in the music that supports the melody; and that's how we get pieces with beautiful use of counter-melody like “The Bunnies,” “Atlantis” and countless other examples in video game music. Here are some more pieces of video game music with counter-melody...can you spot those moments just by listening? Can you find more examples in video game music that I haven't listed here? I'd love to hear them! New Super Mario Bros. Wii - Staff Roll Legend of Zelda: Windwaker - Staff Roll Ar-tonelico - Singing Hill Star Fox - Main Titles Enjoy this week's transcriptions of Atlantis and Grunty Industries from Banjo-Tooie! More on the way!

9 Comments

|

AuthorVideo game music was what got me composing as a kid, and I learned the basics of composition from transcribing my favorite VGM pieces. These are my thoughts and discoveries about various game compositions as I transcribe and study them. Feel free to comment with your own thoughts/ideas as well! Archives

July 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed