|

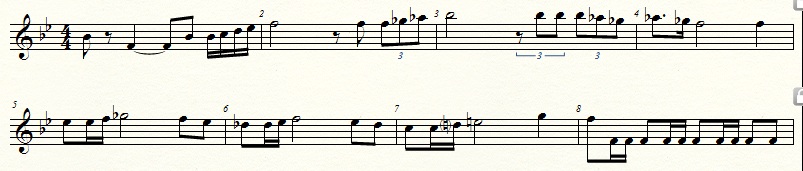

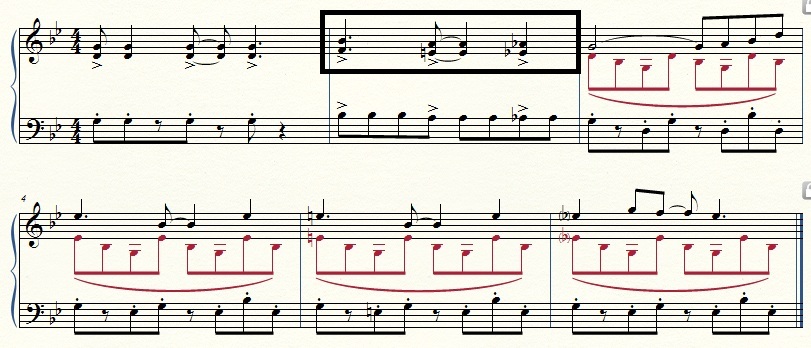

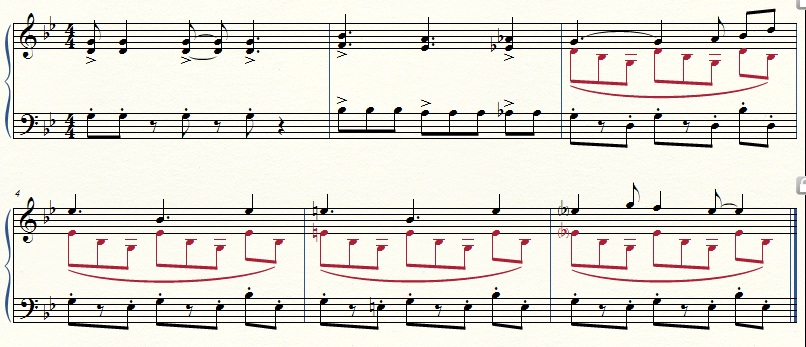

Hello all! Stay tuned this weekend for another installation of my podcast segment Between the Lines, on Overclocked Podcast! Since last I posted here, I've had a total blast working on this project with my friend and podcast producer Stephen Kelly--he's an absolute wizard at splicing all of my audio together and I seriously can't thank him enough for the beautiful job he's done on the most recent segment about Ganondorf's Theme in various Zelda games. I mentioned in the podcast that I would upload sheet music with some music theory notes to illustrate what I talk about in the segment, so go ahead and click that link below if you'd like to check it out. Thanks so much for listening everyone, and thanks again Overclocked Podcast for having me on the show!

4 Comments

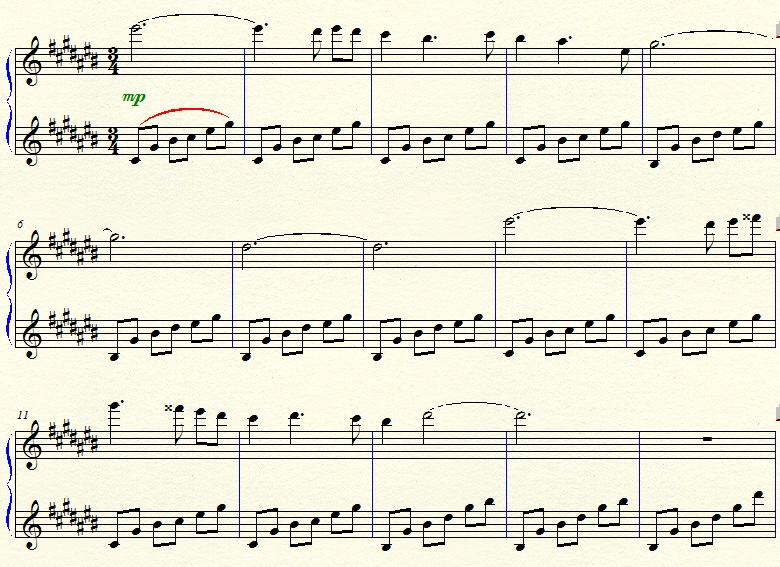

Hey all! 3 years is an embarrassingly long time to let pass on without any updates on this blog. But hopefully this will cheer up my fellow music theory nerds aching for geeky posts about compositional techniques in video game soundtracks: I've been appearing on Overclocked Podcast with a segment called Between the Lines. I was invited by Stephen Kelly to put together a segment similar to my blog posts, in audio form. And I have to say, I've absolutely fallen in love with this new format of talking about music theory! I put together about one episode per month, and with the help of Stephen's mad editing skills, it's been MUCH easier to keep up with my hobby of dissecting video game music. Not only is it much faster for me to record my speaking voice than to edit these blog posts, but I think it's also easier to discuss and demonstrate examples within the episode. While I could create sheet music for visual examples on this blog, it was always a little awkward and time-consuming to put together audio to go with it. Stephen is a HUGE help in slicing and editing all of the audio examples together in the blog posts, and I can sing or speak counting/motives/etc. when illustrating points about rhythm, melody and so on. Here are the casts I've done so far: My hope is that as I create these episodes, I can post visual examples of sheet music here to go along with the audio. It's going to depend on how much free time I have, but bottom line, I'm really glad that I've been able to continue my blog on the podcast! So for now, I'm going to be updating this blog with links to the episodes, and hopefully, occasionally some sheet music to go along with it. Thank you so much to Stephen and the Overclocked Podcast crew for having me on the show, it's been such a blessing to be able to continue this really fun and fulfilling hobby with their help and support!

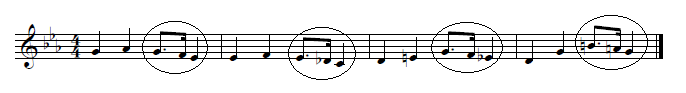

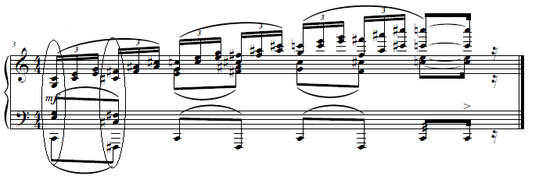

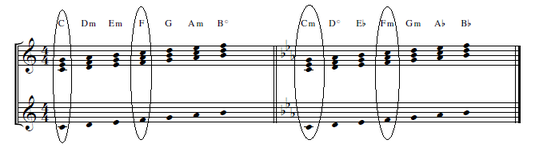

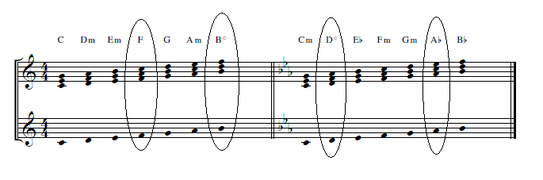

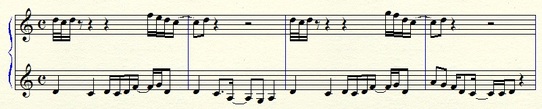

Thanks again for reading everyone :) Looking forward to updating soon! Hey guys...it has been a really, really, REALLY long time *wince* I hope my absence hasn't offended any fans of this blog! Believe you me, it hasn't been due to a lack of creativity or ideas for new articles--I have a list about a mile long of dorky musical things to write about! Life just grows increasingly more hectic as I try to balance all of the different hats I wear, plus my summer internship in LA with a few video game/film composers. It's been a fun ride so far, and I've been learning a ton. I sure have been missing this blog though, so I hope to be getting back in gear with this and writing more often. So let's get down to some musical biz-ness! For those of you familiar with my quirky sense of humor, it probably comes as no surprise that Banjo-Kazooie is one of my favorite game franchises of all time. The sense of humor is right up my alley, and I love everything about it from the artwork to the gameplay to (of course) the music, composed by Grant Kirkhope. I actually grew up with many games featuring Mr. Kirkhope's scores, without even realizing it! Goldeneye 007, Donkey Kong 64, Perfect Dark, and of course B-K and B-T. I've been DYING to write this post for a while now, and I've finally managed to scrape all of my thoughts together into what is hopefully a cohesive article! For those of you unfamiliar with this particular bird and bear: B-K was a platformer, very similar in construction to one of its contemporaries, Super Mario 64. You traveled to different “worlds” via paintings, and had to collect tokens (musical notes and jigsaw puzzle pieces) to unlock different sections of the central overworld (Gruntilda's Lair). The methods for obtaining the more difficult “Jiggies” involved solving puzzles, fetch quests, racing or battling enemies, etc. It actually sounds a LOT like Super Mario 64 when described that way, so what makes the game different? First of all, the characters and story, of course—and there aren't enough words in the English language for me to describe how ridiculously silly, fun and downright hilarious this game is to me. There is a witch doctor character named Mumbo Jumbo. MUMBO JUMBO. Tell me you don't love everything about that. And in turn, these aspects of story and gameplay inform the musical score. Grant Kirkhope composed the music to accompany the awesomeness, and I seriously cannot convey how much I freaking LOVE THIS SCORE. It has a style and personality that is unlike any other game to me; and it's not like he was trying to break new ground and write crazy orchestration, or wildly atonal tracks. On the contrary, the melodic construction is very simple and straightforward, easy for the ear to follow. It has a few harmonic twists and turns, but not in a distracting way. In fact, one of the most important things to keep in mind when writing music for open-ended, non-linear gameplay is the fact that, depending on the difficulty of the game/the skill level of the player, he/she could be stuck there for hours. Or if you're like me and simply could NOT figure out how to open the door into Grunty Industries, for DAYS. And with nine different worlds plus several other locations, character themes, etc., that's a lot of music. And therein lies the challenge. Compare a game to an opera; both can be short works with appropriately short scores, or they can be large-scale works with several hours worth of music. For the latter, whether it's a game or an opera, the challenge is the same: how do you create one piece out of all of that music? How do you create a single, long work that takes hours to fully experience, without losing the attention or understanding of your listener, or feeling like several smaller pieces that don't connect? The answer is always different, and that's why we study and analyze music. In the case of Banjo-Kazooie, the answer for me is: the harmonic motive. This is the sort of thing where the brilliance comes from it simplicity; you hear it, you notice it but don't know how to put words to it. Let's see how Wikipedia did: A harmonic motive is a series of chords defined in the abstract, that is, without reference to melody or rhythm. That's possibly a bit confusing at a first glance; let's break the definition down. What does motive mean? It's the stem of another word we use more often: motivate. When a person is motivated, they are driven by a purpose, idea, or goal. A musical motive is essentially just that: a musical idea that drives the content of a piece. Whether it's melodic, harmonic, rhythmic, etc, it's simply a small, short idea on which a composition is based. It can be melodic: Or rhythmic: Sometimes, a mixture of those two. Or--it can be harmonic. This one is trickier, because it must defined outside of melody and rhythm. It is not, in-and-of-itself, a complete chord progression, but rather a small chunk on which a progression may be a built. Banjo-Kazooie is a PERFECT EXAMPLE OF THIS. I tried to find the simplest, most straightforward use of the motive in the game, and the first one that popped into my head was the musical cue for unlocking a World Door. Have a listen: Whether you read music or not, that looks pretty horrifying--but even just from listening, you probably noticed that it's simply the same two chords repeated over and over, C Major and F# Major. I circled it in the first beat, but it continues throughout the entire measure. Listen to it again, focusing on the bass note--it just oscillates (switches) between C and F#, making the chord change easy to hear. This particular interval (distance between two notes) of six half-steps is called a tritone. It has a very distinctive sound, doesn't it? For those of you who have played B-K, it may sound familiar. That's because you hear it throughout the entire game. ALL. THE TIME. Those are just a few examples from a few pieces in B-K and B-T; the chords built off of the tritone are either both major or both minor, so the chord quality sounds different in some of the examples; but the interval between the chords sounds the same. Now let's get specific: why do we recognize these chords? Why do they have a more unique sound than any other pair of chords in Grant Kirkhope's score? The technical, music theory reason is: this chord relationship does not naturally appear in major/minor scales. For example, the World Door Open theme is in good ol', traditional C Major. In the keys of C Major (and C Minor), the necessary pitches for any kind of F# chord (major or minor) do not exist: This is not to say the tritone itself does not exist. Looking at the major scale, you may have noticed that the F to B relationship is six half-steps; in the minor scale, the D to Ab as well. But you'll notice that the chords built off of those pitches are not BOTH major or minor. One of the chords is diminished. Building two major/minor chords off of the interval of a tritone requires the composer to borrow pitches from outside the scale--and THAT'S what makes this chord relationship jump out at us. And since the entire score to this game is clearly composed in major/minor, this particular chord relationship with their entirely unique sound immediately leaps out to us, making it an incredibly powerful harmonic motive. It's instantly recognizable when you hear it....and yet not distracting, at all, because the motive has been woven so tightly into the fabric of the score, as you heard in the above examples. But to REALLY answer the question “Why these chords?”, we should go directly to the source, Mr. Grant Kirkhope himself. And thanks to my complete and total addiction to Game Grumps, we can! (Jump to 55:03 for his discussion of the motive--but I HIGHLY recommend you watch the entire thing!) Amazing how such a small, elegantly simple decision can color an entire score and enhance the story that much more. Love it :)

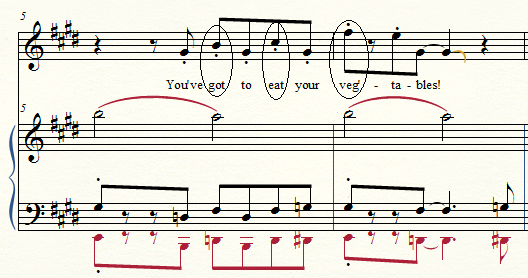

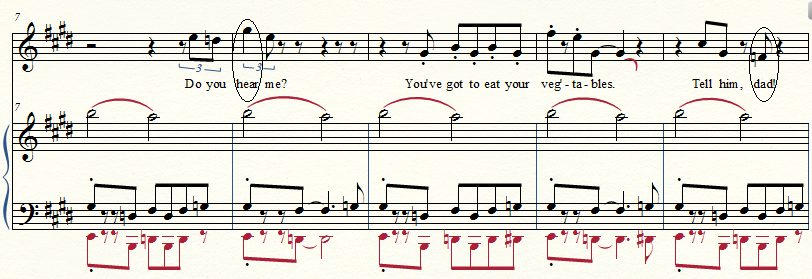

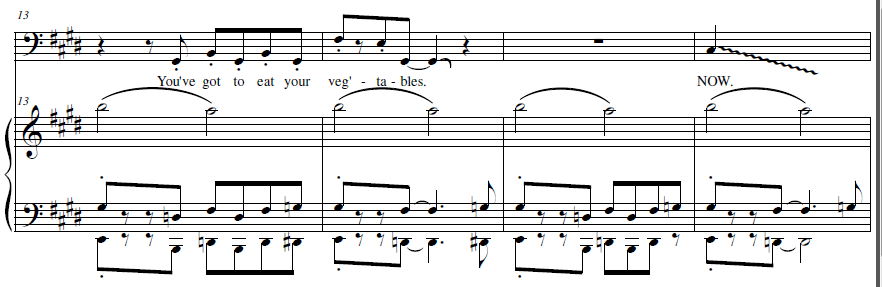

Enjoy this week's transcriptions of Gobi's Valley (Histup) and World Door Open from Banjo-Kazooie, and Going in Circles from Bio Menace! More on the way! Hello friends! Sorry this post is a bit late--I meant to have this done last week, but last week was pretty brutal! When I'm not on the road with VGL, I work as a singer/pianist for various churches on Long Island. This past week, Catholic churches were celebrating Ash Wednesday, for which I was hired to do four gigs in Queens, Brooklyn and Nassau County. All of them involved playing the organ. It was a terrifying day for two big reasons: 1) I'm only just learning to play the organ over the past month or so, and 2) I had a nasty cold that reached its zenith on that very day. I croaked my way through the masses and managed to play the pedals without falling off the organ bench, so we'll call it a win :-P But the cold took a lot out of me, I didn't get as much writing done this week. So, this is going to be a pretty short post, but hey, maybe that's a good thing after the NOVEL I wrote last week :-P So, last Tuesday night, I was coughing up a lung and couldn't get to sleep because of my screaming sore throat. Like the hopeless geek I am, I decide that to help me sleep, I'll pick out some video game music and transcribe until my brain goes into a cold shutdown and I pass out. As I booted my computer, I immediately thought of the old DOS games I used to play when I was in elementary school. My sister and I were DOS addicts, we loved all of those old games—Word Rescue, Math Rescue, Monster Bash, God of Thunder, Lemmings, and of course, Commander Keen. He was definitely one of my favorites! I loved the silly story, fun gameplay, the catchy music, the Dopefish. How can you not love a game that has a creature called “the Dopefish?” He was the terror of the deeps, and to this day, I don't believe I have ever beaten Dopefish level. So, I started Youtubing the music. I was pleasantly surprised to discover that the songs actually had titles, instead of just “Level 1, Level 2” etc. One of the Youtube videos was called “You've Got to Eat Your Vegetables.” I clicked it, and laughed when I recognized the tune—it happened to be the music that accompanies the Dopefish level. Then I gaped at the Youtube video description. An interview with Bobby Prince in the 90s revealed that this wasn't originally a piece of instrumental music; it was a song. WITH WORDS. THE DOPEFISH THEME...HAD WORDS...*EXPLODE* Apparently, Bobby Prince, the God of Music at iD software, had written this piece to accompany a completely different installation of the Commander Keen series. The game was supposed to begin with a cutscene of Billy Blaze at the dining room table, refusing to eat his vegetables. I'm just guessing from what Bobby describes in the interview, but it seems that this song was meant to “vocalize” the words, which I'm guessing would just appear as text at the bottom of the screen. I say “vocalize” because I'm assuming no one was actually going to sing the lyrics; the gamer was most likely going to read the text while hearing the melody, and his/her brain would automatically link the two together. But Prince didn't just write a random melody and slap some words on it; he reflected the inflection (speech pattern) of the characters' voices through the contour, or "shape," of the melody. All melodies have a shape of some sort, but it is more important than ever when you're setting words to music. The English language has a natural rhythm to it; our voices rise and fall when we talk because some words in a sentence are more important than others. So, when writing a melody to go with lyrics, composers have to keep that natural word stress in mind, to make sure that they aren't musically stressing the wrong words. And Prince does this perfectly! Take the very first line of the son. Billy's mother is the first one to yell at him; what would an exasperated mother sound like if she was telling you to eat your vegetables? She wouldn't just say "Billy, you've got to eat your vegetables" in a monotone; it would be something like, “BILLy! You've GOT to EAT your VEGetables!” There are certain words and syllables in that sentence that are stressed, right? Now listen to the melody line. He stressed those words and syllables in the melody line by placing them on higher notes--the rise and fall of her voice is exactly reflected in the rise and fall of the melody-line. Then she says, “do you hear me?! You've got to EAT your VEGETABLES!" Appealing to her husband, "Tell him, Dad...” Prince expresses the exasperation in her voice through that random F-natural on "Dad." Then here comes Dad, with the same exact melody—only now the melody-line is taken down two octaves, to reflect a man's lower voice. He says, “You've got to eat your vegetables. NOW.” Check out that glissando—great way to express the command in his voice as he says “NOOOWWW!” Lastly, here comes Billy's little sister, teasing him at the table. Now the melody-line has been taken up two octaves, to reflect a little girl's voice. And we have the classic teasing sound; Prince adds those extra halfsteps to it to make it sound a little more grating: How cool is that? Without any spoken/sung words at all, the contour of the melody conveys EXACTLY what Billy's family sounds like when they speak to him; exasperated mom, fed-up dad, and giggling little sister. And then you have the supporting accompaniment itself; the tempo is deliberately slow and draggy, the instrument sounds are heavy and clunky--all of this clearly represents Billy's boredom and complete lack of will to eat his vegetables. And nobody even said a word. Hail to the Prince, baby!

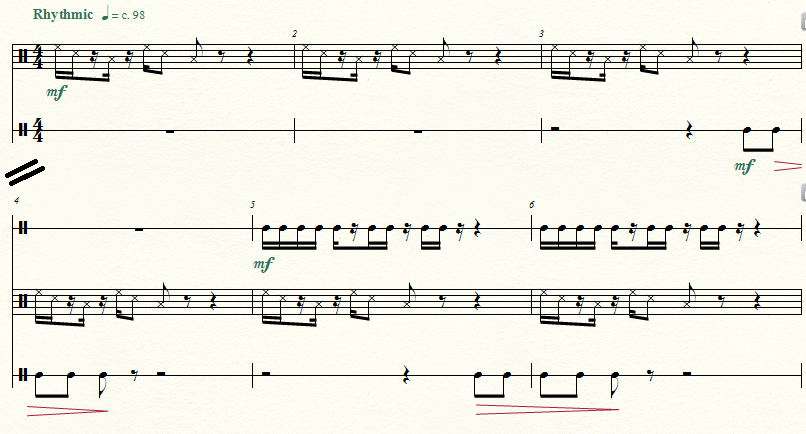

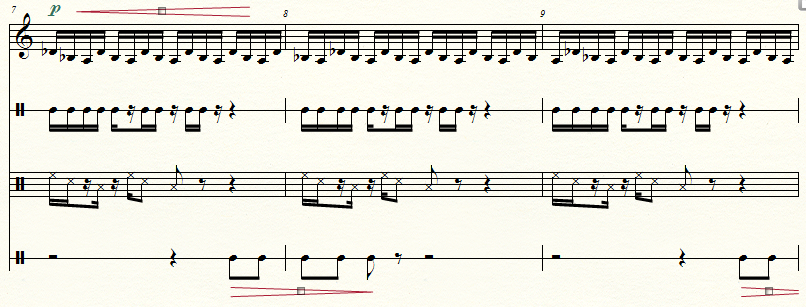

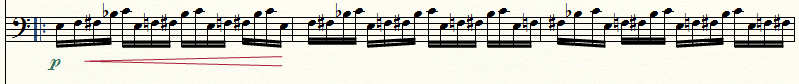

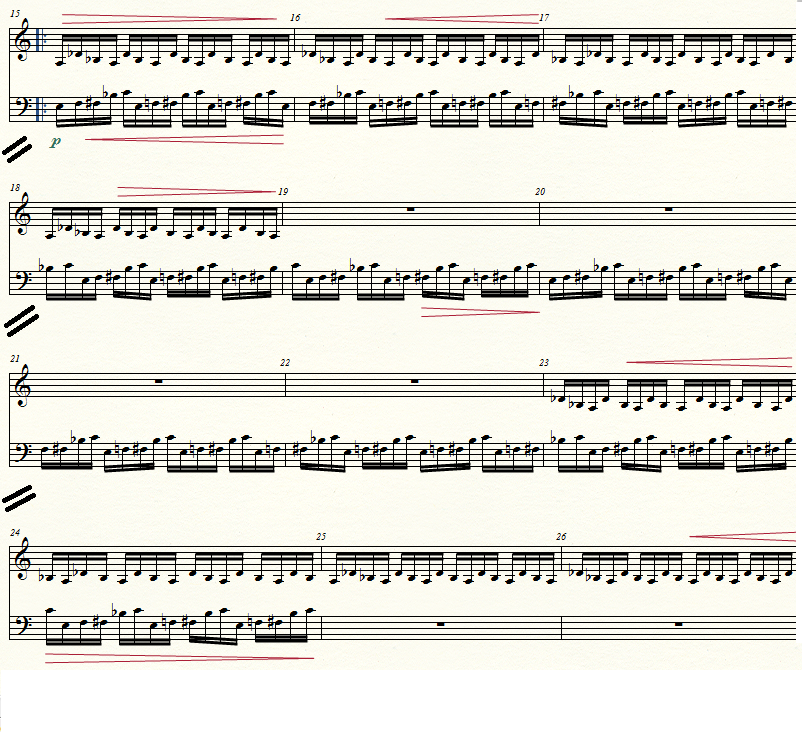

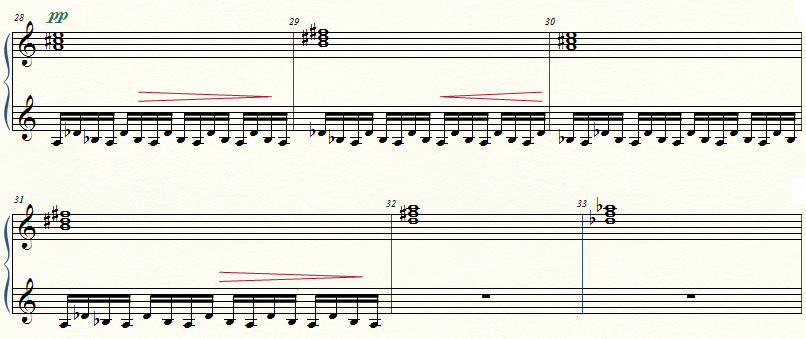

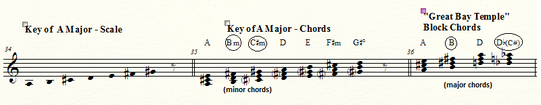

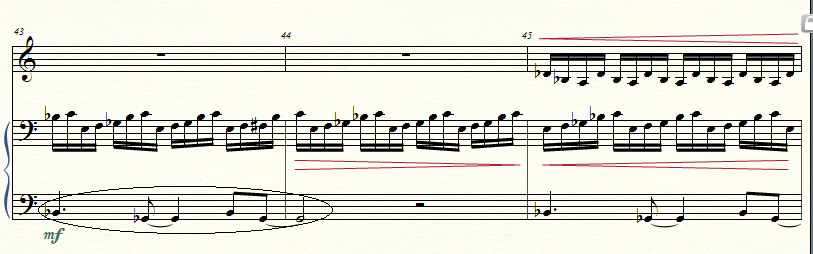

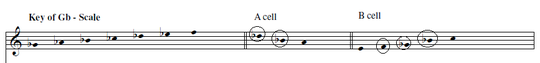

Enjoy this week's transcriptions for You've Got to Eat Your Vegetables and Map Theme from Commander Keen 4, and Laboratory from Bio Menace! More on the way! Hello friends! I hope you've put on your thinking caps this week, because this post is going to be down and dirty with some intense music theory. I'm trying to keep this Blog fresh by coming up with different formats for the articles; last week, I picked a musical concept (the counter-melody) and we looked at a few pieces from different games that used it to great effect. This week, I thought I'd try doing a full-fledged theory analysis of just one piece from a video game, and pick apart all of the different musical elements within it. And I've just been DYING to dig into this piece for a while now: the Great Bay Temple theme from Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask. Not exactly music we'll be hearing live in concert anytime soon, eh? :-P This probably is not considered one of the more well-known pieces from Majora's Mask, and the game did not have a ton of new music to begin with. Not that this is a bad thing, but--the soundtrack felt much smaller than its predecessor Ocarina of Time. It wasn't just that they re-used a lot of music from OoT; they also re-used a lot of the same themes within Majora's Mask. Clock Town, the center of Termina and thus where you spend a lot of your time, has the same theme from day to day (rehashed to reflect the weather and circumstances); the cursed areas outside of Clock Town also used the same “Majora's Theme” simply with different instrumentation; and the temples' music was on the reeeeally murky and ambient side—but then again, this entire game was really out of left field for the Zelda franchise. And what a gem it was! I loved the darkness of the story, the strong theme of the meaning of friendship, and the challenge of the side stories and side quests. This game really got you to know the characters in Clock Town, and it certainly was nice to have a break from Ganondorf for once, wasn't it? This game did have some new pieces that really added a lot to the game (i.e. the Song of Healing, the End of the World), but I have always considered the Great Bay Temple theme one of my favorites. Ever since I heard it when I was fourteen, it just stuck with me. I'm always drawn to highly rhythmic pieces with a lot of neat percussive effects in it, and this certainly has elements of that—but at first glance, this does not seem like a piece most people walk around humming after they've played the game, right? But when I finally sat down and started analyzing it this week, I discovered there was a lot and I mean a LOT more to it than meets the eye--or the ear, I should say :-P So! Ever since I started this blog, I've been trying to make these posts as “user-friendly” as possible, so people who are non-musicians, or unfamiliar with music theory can understand and appreciate the elements that go into the composition of a video game piece. But the Great Bay Temple theme is a violently erupting volcano of ingenious musical design, and I thought maybe this would be a good time to just go nuts and dig deep into my nerdy, music theory side. I'm going to explain everything as I go along, so don't be daunted if you're not a trained musician!! This article is just going to cover a lot more info than previous blogs. Now, I haven't met any myself, but if those stereotypically snooty, VGM-scoffing musical theorists really exist, then I sincerely hope they stumble upon this article sometime--I'm sure it would surprise them to see just how much depth and integrity that video game music can possess :) The Level Design A little backstory, for those who are unfamiliar with the game: Great Bay Temple is the token Zelda water temple. Now, the challenge of the Water Temple in the previous game (OoT) was navigating an area in which Link was ill-suited to travel: it was filled with water. Your choice was to either put on the 400-pound boots and walk around really slowly underwater, or do the Unheroic Side-Stroke. It was annoying and difficult. However, in Majora's Mask, Link has just obtained a mask that allows him to turn into a Zora (fish-creature), which means he'll be moving easily and rapidly through the water. The challenge in the Great Bay Temple is that it is designed around a series of water pumps attached to underwater propellers, which change the direction and flow of the water into tunnels leading to different areas of the dungeon—so as tempting as it is to zip around in your Zora costume, you have to be careful not to get sucked into the wrong tunnel. So, in summary, the basic elements of this temple: Speedy travel with the Zora mask. Giant tanks of water. Water pumps, controlled by gears. Propellers moving the water. Rapid currents of water, sometimes in opposing directions. Now listen to the song again. There's a lot of musical imagery to support the environment and design of the temple; let's walk through the piece step by step and figure out how this was done. The Ambience The piece starts out with a simple ambience (atmospheric sound), a machine-like hum. Link is essentially in a giant pumping station, so ambience is obviously a good fit. Then the drum patterns start up. The first drum sound has a hollow ring, as though banging on a large, empty cannister, or oil drum; the second sound reminds me of the crash of heavy machinery, and the third is almost electronic in nature. On a whole, the drum patterns have a very mechanical, factory-like vibe to them; while they are the driving rhythmic force of the piece, I would say that the choice of drum timbres (colors) adds also to the ambience that the composers are going for: inside a machine. Polythematic Composition Then at m.7, we've got our first actual pitches (which I call the “A” theme): Before we go on, let's review the definition of melody, courtesy of Wikipedia: “a linear succession of musical tones which is perceived as a single entity. In its most literal sense, a melody is a combination of pitch and rhythm.” Look at the A passage. Not very striking melodically, is it? In fact, I wouldn't call this a melody at all. What we have here is not a deliberately constructed combination of pitch and rhythm; what we have here is simply 3 notes repeating over and over again. at the same rate of subdivision (in this case, sixteenth notes). To top it all off, the pattern does not divide equally into the time signature. If I rebeamed this passage to reflect the 3-note pattern, it would look like this: Because the pattern doesn't divide evenly, that means each measures has a different pitch of the cell as the downbeat (first beat of the measure). As a result, there is no specific rhythmic importance attached to these notes at all; they just loop continuously. So if this isn't a melody...what is it? In music theory, we would call that group of 3 notes a cell. Wikipedia defines a musical cell as “the smallest indivisible unit of rhythmic and melodic design that cn be isolated, or can make up one part of a thematic context.” What is a theme? Also according to Wikipedia, it is “the material, usually a recognizable melody, upon which part or all of a composition is based.” This passage is certainly recognizable, even if it is not what we would call “melodic.” So, what we have here is a theme, based off of a 3-note cell. BUT WAIT. Going on to m.15, we see another, different theme start up. Let's call this one B; have a listen to just the B theme, isolated: Take a look at the notes; we have another repeating pattern. This one is based off of a 5-note cell, also repeating on a 16th note subdivision. Being a 5-note pattern, it also does not divide evenly into the time signature. What happens when you put the two themes together, as in m.15? MADNESS: Since there are two different themes that make up this piece, we would call this...wait for it...a polythematic composition. Pretty neat effect, right? Not only are the themes played by the same instrument, but they're also in the exact same register; they weave in and out of each other, and since the cells are different lengths (3 and 5), they never line up in any sort of rhythmic way. It's a very cool, watery, murky sound. Harmonic Planing and Implied Keys Now for the last few elements that make up this piece—until now, we've just had ambience, drums, and two conflicting, unrelated themes. We do actually have brief moments of harmony at the end of the piece. In m. 25, everything drops out completely and we're left with just the A theme; then, very faintly, we hear flute-like block chords. The first chord is an A major chord (A, C#, E). Now, since the notes in the A theme do contain C# (Db), and A, my ear automatically tells my brain, “Well, we must be in the key of A major!” But some of those chords do NOT belong in the key of A: In a major key, there are naturally a few minor chords; but all of the chords in the passage are major. How was this achieved? Every note in the chord moves the exact same interval (distance) to the next set of notes. This kind of parallel movement of notes is called harmonic planing, or parallel harmony. What does this do? In this case, it prevents us from hearing a definitive, actual key signature. But before we chalk this one up to a simple case of harmonic planing, check out that last block chord, a Db major chord. Then look at the notes in m. 43--a Bb and Gb, implying a Gb major chord (Gb, Bb, Db) The Db in m.33 is the dominant chord of Gb. Very, VERY simply put, the use of these two chords, in that order, could imply that we are in the key of Gb at m.43. And it's JUST a few measures after this that the entire piece starts looping. Now try THIS on for size: let's look at the seemingly random 3 and 5 note cells for the A and B themes. They seem conflicting at first...but if we look at the pitches in the context of the key of Gb... We are...ALMOST in the key of Gb. Almost...but enough of the pitches in the cells are from outside the scale. As a result, the key of Gb is obscured for the entire piece...until those pitches in the bass at m.43.

So this seemingly arbitrary choice of harmonic planing in mm.28-33 actually could be construed as setting up the key for the ENTIRE PIECE: Gb. The Summary (Here's hoping you're still reading) So! Now that most of you are bored to tears and are trying to remember why you thought it would be fun to read this blog: what does all of this mean musically? We've discussed the piece in the most dry, emotionally-removed music theory terminology available; we know now that there was actually a lot of cool stuff going on throughout the composition. Now let's connect the pieces and see what this music adds to the game.

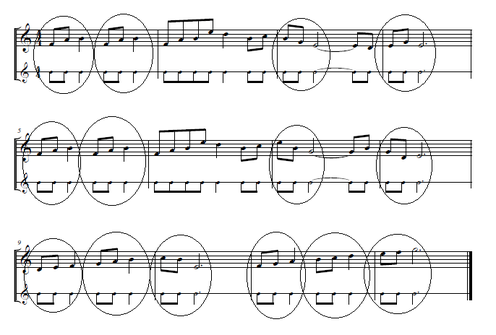

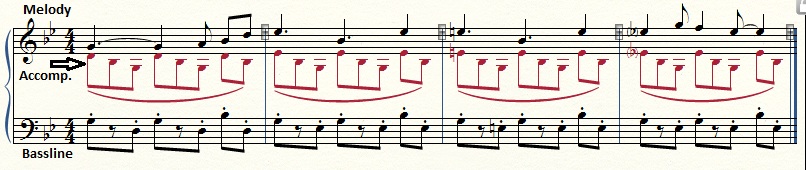

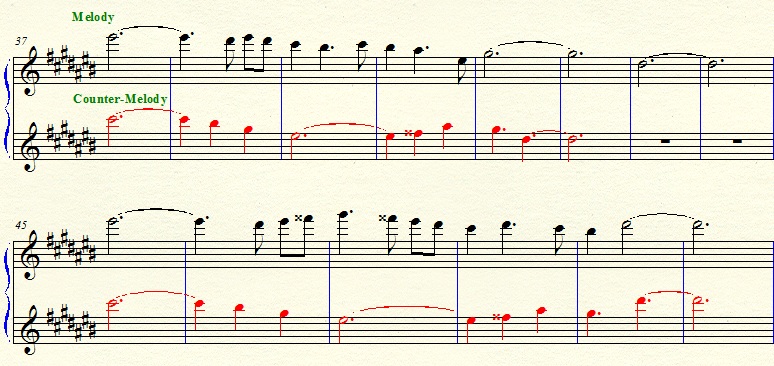

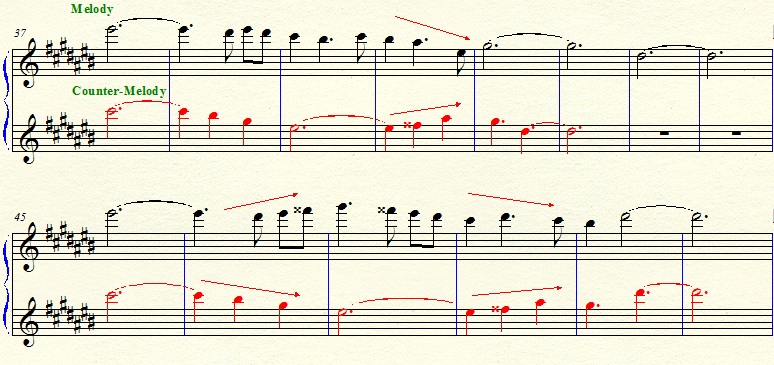

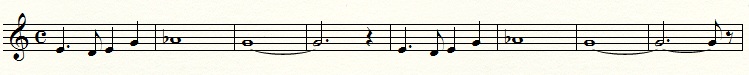

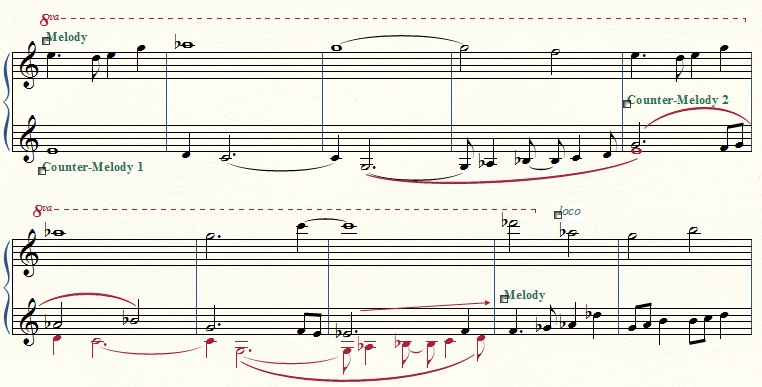

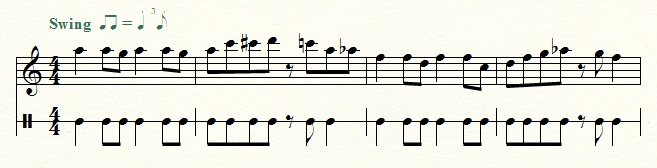

You know what my favorite part of this piece is? How elegantly simple it is. We have like what, 5-6 different instrument sounds, including the percussion? Two straightforward themes, a moment with harmonizing chords, the simple background ambience? And while the piece was certainly memorable to me, it never distracted me from the gameplay. The music was meant to be a supporting feature, not the main event. And how did Kondo and Minegishi do this? With a brilliant mixture of just a few elements, like the recipe for a cake. I can make an eight-tier wedding cake and recreate the Mona Lisa on it with fifty-seven different shades of icing; or, I can throw some flour, sugar, butter and banana in a bowl and make my grandmother's plain-looking but ridiculously tasty banana cake. You don't always need a lot of bells and whistles to make a really great piece of video game music; the “greatness” of a piece comes from how effective it is in the level, and I think the Great Bay Temple music has certainly done that. What do you think? Enjoy this week's arrangements of the Dungeon/Underworld theme from the original Legend of Zelda, and Great Bay Temple from LoZ: Majora's Mask! More on the way! Let's change things up a little! Instead of talking about one game in particular this week, let's talk about a musical concept and how it is applied in games from different series. This is a big post I had a lot of fun writing about, because it's a really neat concept that can be really powerful when used correctly: the counter-melody. Wikipedia says the definition of counter-melody is “a sequence of notes, perceived as a melody, written to be simultaneously with a more prominent lead. Typically a counter-melody performs a subordinate role, and is heard in a texture consisting of a melody plus accompaniment.” What does all of that mean? Basically, a counter-melody is exactly what it sounds like: it's a secondary melody that is meant to “counter” the primary melody. It generally follows a totally different rhythm and contour (shape) than the primary melody, so that it stands out in the texture. A lot of the classic game tunes feature a “melody & accompaniment” form, like in Zelda II's “Palace Theme.” The middle line of music is obviously supporting the melody; it is not a melody in and of itself, but simply an accompanying pattern that lies underneath the melody. A counter-melody is different in that it would also have a melodic character of its own. The strength of using a counter-melody in video game music is that it adds variation to a repeated melody. Let's face it, most video game music HAS to be able to loop endlessly, right? A counter-melody is a great way to prevent the theme from getting old. A counter-melody can make the original melody sound way more interesting, by highlighting the differences between the two. Before we look at Banjo-Tooie's “Atlantis,” one of this week's new transcriptions, let's bounce back to a piece I posted a while ago, “The Bunnies” from Super Mario Galaxy. This is a freaking PERFECT EXAMPLE of how counter-melody works, and in a really lovely, mystical way. First, take a look at about half of the primary melody of The Bunnies. Check out the bottom staff in the piano; obviously just accompaniment, right? We wouldn't describe that figure as being melodic in nature—the repeated pattern is actually closer to an ostinato. Now let's jump ahead in the piece: Check out that second line. It's not simply arpeggiating chords, it has a distinctive shape and character of its own, completely unrelated to the primary melody. The primary melody is much more rhythmically active, on a punctuated harp string sound; the secondary melody has a fuller, sustained sound and less rhythmic activity. Each melody tends to move in opposition to the other; i.e., when one goes up, the other goes down. Now what does this mean musically? What does this convey to the listener? Here's my take on it, my own opinion: The primary melody kind of hops around innocently on that high harp sound, so for me, it represents the bunnies. The secondary melody sounds a bit softer to my ears, and is much more sustained and has a —for lack of a better word--”sci-fi” kind of synthy sound. This is just my own take, but it gives the piece a feeling of weightlessness for me (weightlessness...loss of gravity...HEY WAIT WE'RE IN SPACE). The sound design in and of itself suggests a feeling of wonderment to me, like a child exploring a new world. In the game, Mario has just woken up on a strange planet after being blown into space by Bowser; he wakes up and encounters space bunnies who encourage him to catch them. The purpose of this scene is to give the player more practice with Mario's game controls; so, not only does the music convey the dramatic content of the scene (“Where am I and who are these bunnies?”), it also reflects what is happening for the player him/herself: exploring the controls and the new space world you find yourself in. It's an innocent song, which conveys to the player that he/she can freely experiment with the controls without fear for Mario's life. It's pretty cool how much a simple counter-melody can add, isn't it? Let's look at some more examples. First, “Atlantis” from Banjo-Tooie. Primary melody: Now let's jump ahead to where the counter-melody comes in. Oooooh, something neat is going on here! The melody is obviously in the high flute, and in the lower flute at m. ___ we have what sounds to me like a long, sustained counter-melody. Then, at m. 39, ANOTHER counter-melody splits off of the first one. It only lasts for a few measures until m. 9 of this example, where it takes over the primary melody-line. Now the high flute has a supporting role, the low flute is the primary. It all happens in the span of just a few seconds and the result is seamless, each melody-line weaving in and out of the other (Like fish swimming in the ocean, OH SNAP!) One more example! This is from a personal favorite tune of mine, “Forest Frenzy” from Donkey Kong Country. Take a listen to the entire song here, see if you can pick out the counter-melody just by listening. Hopefully you caught it on that first hearing! Now check it out in the sheet music: Now, for me, the counter-melody does not stick out as strongly in this piece as in the other examples. This piece has a LOT of ostinati in it—those repeating rhythmic and chordal figures make up a lot of the catchiness of the song—but as a result of the repetitive nature of the texture, the counter-melody is kind of lost. It isn't as different from the melody as it could be. In fact, it's almost tempting to call it simply some sort of accompanimental figure—but the fact that it is a single-line melody (one note at a time) and it's in a higher register than the primary melody makes me think that this was intended to be a counter-melody. Not as prominent as the other examples we looked at...but maybe that was the point. This piece is highly rhythmic and the melody is not necessarily the most important feature. So the weaker counter-melody doesn't really take away from the piece, but helps the melody blend in with the rest of the texture.

That's a lot of information to digest, but hopefully you get the idea of all the different ways a counter-melody can function. To finish this ginormous post off, I want to quote a very famous poem by William Carlos William. “It is a principle of music / to repeat the theme. Repeat / and repeat again, / as the pace mounts.” This is more true than ever in video game music, a medium that requires musical looping for the player to have freedom to play at his/her own pace. It is how composers vary the theme, to make it different each time we hear it, that enables us as listeners to not become bored with the same thing over and over again. The video game world has a history steeped in extremely strong melodies—melodies so catchy that you can hear it literally a thousand times and not get bored—but as the hardware grew, so did the capabilities of the composers to create music with more variation. I mean, what was the average length of the typical video game song in the 80's, like one or two minutes? Now we have composers creating much longer pieces with more depth in the music that supports the melody; and that's how we get pieces with beautiful use of counter-melody like “The Bunnies,” “Atlantis” and countless other examples in video game music. Here are some more pieces of video game music with counter-melody...can you spot those moments just by listening? Can you find more examples in video game music that I haven't listed here? I'd love to hear them! New Super Mario Bros. Wii - Staff Roll Legend of Zelda: Windwaker - Staff Roll Ar-tonelico - Singing Hill Star Fox - Main Titles Enjoy this week's transcriptions of Atlantis and Grunty Industries from Banjo-Tooie! More on the way! “Music theory” can be somewhat of a polarizing force in music school ;-) Some people love it, some people despise it with every fiber in their being. The reason for this is that music theory involves staring at scores for long hours and analyzing each and every note for connections to each and every other note in the score. It can quickly become visually and mentally exhausting. And most students have trouble with the “ear-training” aspect of it; there's sight-singing, where you have to sing a melody line that you've never seen before, on the spot, in front of your entire class. Or dictation, listening to a piece you've never heard before and having to write down the melody and bass line by ear. It's very challenging, and the fact that most public schools only offer music theory courses in high school doesn't help. Learning to read and comprehend music is like learning a whole separate language—it's harder to learn as an adult, rather than as a child. Me, I was lucky in school! I enjoyed the sight-singing, dictation and ear-training courses because it's something I had been doing ever since I was a child. I started transcribing video game music as hobby when I was just 10 years old, because I wanted to be able to listen to the music without having to play the games. So when I started my first music theory courses in high school, I was surprised to discover that my ear-training was already very strong, at a more advanced level than most of my class. But even with that solid foundation, score analysis still would have my head aching and my eyes rolling after about half an hour. It's true that composers write with a form in mind--they create melodies and themes that work well together, have them connect in some way, use certain distinct elements to build the fabric of a piece, etc. So, it's always, always worth it to look at a score and discover the individual elements that make up the music; it's like looking at the blueprints of a machine and figuring out how all the parts work together; with that knowledge, you can start building your own machines! But the flipside is that you have to be careful that theorizing doesn't completely take over—all of a sudden, you find “things” in the music--motives, phrases, rhythms, intervals--that seem meaningful at first, but were quite possibly accidental, unintentional and had no bearing on how the piece was written. The fact that it's called music theory means you can basically draw any conclusions you want, but I think sometimes a composer chooses the notes not because of some mathematical equation, not because he had used a similar pattern upside down and backwards 400 measures earlier, not because the notes are actually code for the initials of his first girlfriend—he chooses them because he likes the way they sound. It's just plain aesthetic taste. There's also a great deal of intuition involved in composing—putting different elements together because it "feels right," without coming up with some musical formula to support it. Now that we've discussed the ups and downs of music theory :-P let's do a little theorizing! Today we're looking at Donkey Kong Country 2: Diddy's Kong Quest. The DKC soundtracks are some of my favorite of all time, especially DKC2. I have played this game more than any other game I've had in my possession, even more than Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time and Super Mario World. Words cannot convey how much I adore this game. In 2010, I was asked to promote our Indianapolis VGL show by performing some video game tunes at our ticket booth inside Gen Con. I tried to pick songs from all the big franchises that worked well as flute solos, but Donkey Kong proved pretty tricky. To me, the magic of the music came not just from the catchy melodies, but from the colors and orchestration. I use the term orchestration loosely; obviously, the music of the Donkey Kong games did not use a traditional symphony orchestra, but in this case, “orchestration” refers to the specific sounds and timbres that Wise used to produce the melody, harmony, bassline, textures, rhythms, etc. So there I was, listening to various DKC themes. I finally picked out “Snakey Chanty,” which had a fun, fast melody, and while I was transcribing it, I got some major deja vu. Something about the song seemed really familiar, like I had heard it somewhere else. I mean, I knew it was drawn from DKC's Gangplank Galleon with a jazzy twist, but there was something else about it that I just couldn't place. It was killing me—what was it about this song that sounded so familiar? Then it clicked. Take a listen to a bit of “Island Swing” (Jungle Hijinx) for a moment. Check out the rhythmic pattern in the drums, one of the most iconic game themes of all time: Now check out a bit of the melody-line of Snakey Chanty: Notice anything about the rhythm of each song? THEY'RE THE SAME.

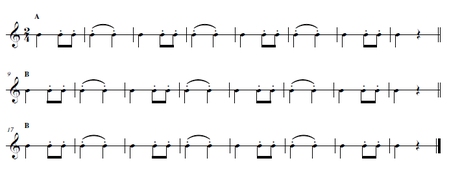

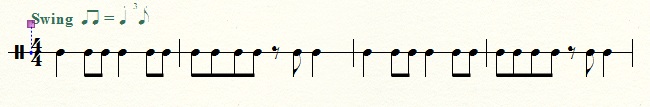

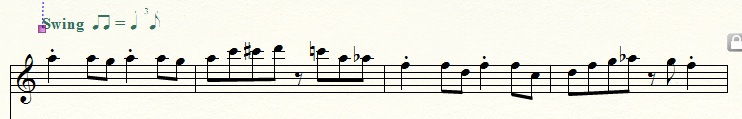

I wanted to punch myself in the eyeball for not noticing the connection right away—the super catchy “Snakey Chanty” from DKC2 is based off of the rhythm of “DK Island Swing” from the previous game! With only slight differences, the rhythm has been transplanted into a totally new setting; originally an earthy jungle beat, it's now a breezy, almost Dixieland Jazz type melody. Wise rehashed an old theme into something brand new, but still totally recognizable. SO! Why did I write all of that stuff about music theory in the beginning of this article? Because I want to make it perfectly clear that is just my theory. Yes, Snakey Chanty and DK Island Swing share the same rhythm, that is a fact. But whether this connection was intentional or completely intuitive on the part of the composer...that's something we'd have to ask David Wise himself ;-) But whether it was intentional or not, I think it was a really ingenious way to musically connect two games in a series, without simply copying the same exact track from one game to the other. NO WONDER HIS NAME IS DAVID WISE. HA-HA SEE WHAT I DID THERE. Enjoy this week's transcriptions of Bayou Boogie, Snakey Chanty and Swanky's Swing from Donkey Kong Country 2: Diddy's Kong Quest! More on the way! Playing Skyward Sword has me in a Zelda mood, so let's take a look at a very popular tune from Zelda II: Adventure of Link! I haven't played the game myself and I'm told that it was not the best game in the Zelda franchise, but the Palace Theme is a favorite tune of many gamers I've met. A lot of video game music in the 80's and early 90's depended on strong melodies to make up for the limited hardware of its time. So, it makes sense that some of the most memorable game themes of all time are from that era. The melodies had to be super catchy, but what is it about melodies that makes them super catchy? What's the “hook” in the Palace Theme that keeps us listening? Let's get a little technical for a second: the definition of “melody” is a succession of musical tones which is perceived as a single entity. A melody, in its most basic form, is made up of two things: pitch and rhythm. So let's look at the first part of the Palace Theme's melody, just the pitches for a moment. Not the craziest melody in the world, right? I'm not saying that it isn't a “good” melody, I personally definitely enjoy it (and it's all up to your personal taste anyway)--but I notice that the melody-line isn't what I'd necessarily call very "active." For a point of reference, let's compare it to a melody like the original Legend of Zelda Overworld. Compared to the Palace Theme, it seems to me like there's a LOT more going on in the Overworld theme, right? The melody has a larger contour (shape), the harmonies and chords supporting it are varied and colorful, the rhythmic pattern with alternating triplets and dotted eighth-sixteenths grabs your attention. Ah-hah, the rhythm! That's just as important to the melody as the pitches—so let's look at the Palace Theme's rhythm for a moment. Right away, in the second bar, we see the rhythmic pattern that will drive the entire piece: dotted quarter, dotted quarter (represented by an eighth tied to a quarter), then quarter. The middle voice has an even stronger role in reflecting this rhythmic pattern—the arpeggios reflect the 3-3-2 pattern as well. If I were to change the beaming of this entire passage to reflect the rhythmic pattern, it would look like this. This is called additive rhythm: when a rhythmic pattern features irregular groups of durations. In common 4/4 time, normally we would just divide each beat into smaller groups; the whole note is divided into 2 halves, the 2 halves are divided into 4 quarters, the 4 quarter notes into 4 groups of eighth notes, etc. This is called divisive rhythm. But in this piece, the rhythm strongly reflects beat durations of 3 eighths, 3 eighths and then 2 eighths—we're adding the smaller beats up to make the bigger groups.

You see additive rhythm most often in asymmetrical meters like 5/8, 7/8—any meter that doesn't divide the beats equally. But as we see in the Palace Theme, additive rhythm can be applied to any type of meter, including the symmetrics. Contemporary composers sometimes notate additive rhythms in the time signatures themselves; in this case, it would be 3+3+2/8. So why didn't I notate it as such in my sheet music? Because there are sections of the piece that do not use additive rhythm. The B section starting at m. 27 is a fluid triplet feel on top of the sweeping 16th arpeggios, which is a really awesome part of the piece as well—by setting up such a strong additive pattern for A section, the B section's more straightforward, divisive rhythmic pattern becomes more noticeable and is a welcome break. Not only that, but the contour of the melody suddenly blows up, it starts a climbing scalar pattern; the rhythm has clearly become secondary to the pitches of the melody. Pretty cool right? In the first half of the piece, the rhythm is the driving force; in the second half, the pitches are the driving force. In this short piece, the composer has highlighted and featured each part of what makes up a strong melody: pitch and rhythm. Bam! Two points for Nakatsuka-san! Enjoy this week's transcriptions of the Main Titles, Overworld and Palace themes from Zelda II: The Adventure of Link. More on the way! I think I was about twelve or thirteen when I first played The Sims. There was something really addictive about the game; maybe it was the fact that I was a child at the time, and being able to live like a grown-up through The Sims was really compelling. It also had some really hilarious touches, like the undead Sims coming back from the dead at night. Let's face it, zombies are always a treat in any medium LOL But there was nothing quite like the day when my perfectly healthy, successful Sim walked out of the giant mansion I had purchased and lovingly decorated for him, walked three-quarters of the way around the house stopped, and writhed and screamed bloody murder for no reason before collapsing to the ground. Then the tombstone and a message popped up, and I promise you I am not making this up: “Oh no! Brad has sadly burned to death. May he rest in peace.” My Sim had died of spontaneous combustion. Now THAT'S ingenious game design.

Anyway: the music! I had actually COMPLETELY forgotten about the music to this game until I was doing some research the other day. I noticed that I have a tendency to arrange a LOT of Nintendo music, namely the Super Mario Bros. series, and I've want to try to branch out to games on different consoles; that's when I remembered The Sims, with music composed by Jerry Martin, Marc Russo, Kirk R. Casey and Dix Bruce. I typed “Sims music” into Youtube, loaded the track to “Buy Mode 1,” and suddenly I was overwhelmed with a tidal wave of nostalgia. There really is nothing like rediscovering something from your youth, especially music. Up until the moment I pressed play, I had no recollection at all of what The Sims music actually sounded like, but the moment the track started, I was able to hum along with the entire song, recalling every note and rhythm. What a unique body of music for a game, huh? It had a wide variety of styles, while still creating a cohesive whole. The Building Mode tracks in particular are a good example; the tracks are comprised completely of solo piano music, but each piece is in an entirely different style. The use of the solo piano in this game is a great example of “less is more.” There is power in a symphony orchestra, choir, wind ensemble—any large ensemble, really, has an incredible, boundless range of colors and textures and can create literally a mountain of sound. However, there is an equally powerful quality to a single instrument playing. Composers write instrumental and vocal solos into large ensemble pieces all the time, and when those moments occur it's really special. To have one, single voice pop out of an enormous texture calls your attention to the individuality of the player/singer, that qualities of their sound that make them unique amongst all of the other instruments in the ensemble. It can also represent something programmatic, like a character or idea that the composer would like to draw your attention to. For example, the violin solos in Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherezade. For those of you who aren't familiar with this freaking amazing masterpiece of sound, it's the story of 1,001 Arabian Nights; the violin solo represents the voice of Scheherezade as she tells the Sultan her stories each night. (I attached a link to the Youtube video, but this is one of those pieces that you simply MUST hear live someday, DEFINITELY check it out if your local orchestra is performing it!) A piano is especially different from the instruments of a symphony, in that it is a polyphonic instrument; it has the capability to play many multiple notes at a time. Some other instruments have a limited capacity for this, i.e. string double stops and woodwind multiphonics, but a piano is literally its own orchestra, if you compose for it the right way. And let's face it, the piano as an instrument that has an unbelievably huge history behind it. It's the instrument of choice for many famous composers such as Beethoven, Mozart, Chopin, Debussy; and even composers who aren't piano virtuosos still use the instrument as a tool for writing their compositions. So, a solo piano can sometimes bring to mind the idea of a composer alone in his/her studio, writing or improvising at the piano. So, with all of that in mind: why the choice of solo piano for the Build Mode? I personally think it's supposed to actually take you out of the game, in a way. I mean, you literally pause the game to go into Build Mode, you aren't actively participating in your Sims lives while in that mode. For me, the solo piano is saying, “your turn, Laura.” It's not about the Sims at that point; it's about you building a home, maybe even a dream home you'd like to live in someday. It's different than creating a musical theme for a person, place, etc. within the context of a story. For example, In Silent Hill 2, the music is ambient, creepy, atmospheric sounds that create a feeling of fear and horror. In Banjo-Kazooie, the bright, cheerful melodies, quirky harmony and downright silly instrumentation (tuba & piccolo FTW) creates the happy world that Banjo and Kazooie live in. The main theme of Legend of Zelda that we all know and love is suitably heroic for Link. But in all of those games, the music is accompanying a pre-determined plot. In the Sims, you create the plot, characters, world, atmosphere, everything. You are the composer hunched at the piano late at night, only instead of music, you're composing a world for your Sims to live in. There is almost no music in the game except in the Buy and Build Modes; the music in the game is entirely reserved for you, the player, as you create your world. There are no themes, motives or melodies that accompany the Sims themselves; the soundtrack accompanies you, the player. And it's all up to you to build the world that you want. Unless you're like me, and delight in creating stupidly designed structures just to see if your Sim can actually live in it :-D Enjoy this week's arrangements of The Sims' Building Mode 4, Dr. Mario's Fever and Sonic the Hedgehog's Marble Zone! More on the way! Yoshi's Story is one of those games that I remember enjoying immensely, only to discover from reviews ten years later that some critics apparently thought it was a totally lackluster game. Yikes. I hate to admit it, but I always second-guess my own take on a game whenever I read a review by an official “game critic.” I mean, everyone's got their own taste and therefore different games will appeal to different people, but when I read criticism about game controls and the like, I start to think, “Gee, maybe I wasn't 'supposed' to enjoy that game, if there were so many people found it disappointing or badly constructed.”

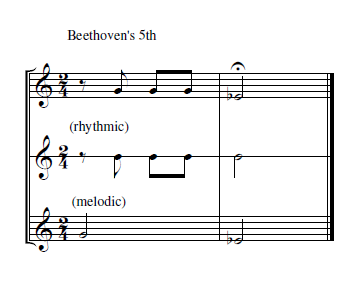

Honestly, though, I think much of the criticism had to do with the extremely childlike atmosphere, and not really “fitting in” with the Mario franchise. I think this definitely comes down to simply a matter of taste. This is the first time we've ever seen Yoshi sans Mario, and I thought it was really cool that the creators made a whole new world with its own ridiculously happy personality. Other games have taken Mario-originated characters in new directions, i.e. the Warioware games. They are awesome in a ludicrous, extremely bizarre way that is entirely unlike your typical Mario game. In the case of Yoshi's Story, I guess it was generally disliked because people assumed it was going to be like Yoshi's Island, which was definitely intended to be considered a major installment of the Mario franchise. But me, I just loved how different the game was! The storybook theme was positively enchanting, and added to the overall cuteness of the game. And I personally happen to love any and all things cute, and Yoshi just might be the Cutest Creation in the History of Cute Things. His voice makes me squeal. His hover-kick makes me giggle. His scream when he falls makes me bawl with laughter each and every time I hear it. And when composer Kazumi Totaka combines multiple Yoshis into a Yoshi choir, I melt at the gloriously endearing sound of slightly-out-of-tune love. All of the music in this game is completely adorable, and that includes Baby Bowser's Lullaby. This theme plays during dungeon levels, and I am CONVINCED that it is a clever musical homage to a Late-Romantic piece of music: Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy. For those of you who are unfamiliar with where this piece comes from, it is a segment of the extremely famous ballet The Nutcracker. I'm sure almost everyone is familiar with at least the name of this ballet, but we are probably most familiar with the pieces that make up The Nutcracker Suite, a concert piece comprised of eight numbers extracted from the ballet. One of these pieces is Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy; take a listen to it real quick. Now go listen to Baby Bowser's Lullaby. Pretty similar, right? Obviously the two pieces begin to deviate after the first few bars, but I'd wager just about ANYONE listening to them would notice the similarities right away. First big question: was this intentional? I have absolutely no idea! But it does seem like an awfully big coincidence to me that the instrumentation, texture and melody line are SO similar between the two pieces. Now for the second big question: if it was intentional, should this be considered stealing? As in, stealing another person's ideas? And if so: is stealing actually bad? Igory Stravinsky once said: "Good composers borrow (ideas from other composers), great composers steal." What does this mean? Basically, composers very often draw off one another for compositional ideas. It sounds a little sketchy at first; "stealing" ideas is something we commonly refer to as plagiarism, and you can get into HUGE trouble for that in the literary world. But just like in literature ,dance, theater or music, artists are free to borrow ideas and rework them in new ways to create new, unique pieces. We hear it all the time when musical artists talk about their influences. I was watching American Idol a few weeks ago and I remember a contestant saying "I'm a mixture of Shakira and early Madonna." Did that bother anyone? Did anyone accuse her of "stealing" those artists' voices? Of course not! Look at all of the songwriters who create songs about their own personal experiences. Their music is influenced by their own lives, so why shouldn't music be influenced by other composers' music? Obviously, you can't steal the entire first movement to Beethoven's Fifth Symphony, but if you liked his idea of the three-note rhythmic motive that is the core of the first movement, then why not take it and rework it in a brand new way? Obviously, there is a point at which borrowing crosses the line into truly stealing. This happens more often in pop music than in classical music. For example, Huey Lewis felt his song "I Want a New Drug" was plagiarized in Ray Parker Jr.'s "Ghostbusters." Even I noticed this one when I first heard the songs. There were a few instances where members of the Beatles were involved in various plagiarism lawsuits. So, you obviously can't take someone's entire song and just change the lyrics, or vice versa for that matter. BUT, there are situations in which it is permitted to directly quote another composer's work in your own. This is aptly known as musical quotation, and it can be done for many reasons; for example, parody, or commenting on another composer's work. In the song “Beethoven Day” from the musical You're a Good Man, Charlie Brown, there are several quotes of famous Beethoven pieces that make us laugh in recognition when we hear them. Quoting in a programmatic work (a composition with an accompanying story, like an opera or a video game) is often done for characterization purposes. For example, according to Wikipedia, using the Star Spangled Banner to accompany an American soldier character, as Puccini did in Madama Butterfly. So now that we all understand the difference between borrowing, stealing and quoting LOL let's get back to Baby Bowser's Lullaby (sheets). Let's look at what similarities the piece has to Sugar Plum Fairy. The instrumentation, for one; the combination of the contrabass pizzicato, celeste and bass clarinet is very distinctive. Next, we've got that pizzicato bass pattern; slightly different between the two pieces, but close enough that the connection can be made. The celeste melody and its supporting chords are also very similar to the original. And the descending clarinet run in m. 10 is a direct quote from Sugar Plum Fairy. The piece deviates quite a bit towards the end—the long, sustained melody is brand new, and there are definitely no castanets in The Nutcracker--but you get my point. This piece is too similar to Tchaikovsky's for me not to assume it was done on purpose. So! Did Kazumi Totaka borrow, steal or quote? My personal vote is that Baby Bower's Lullaby is intended to be a parody of Sugar Plum Fairy by way of quoting. There is a certain dark innocence to Sugar Plum Fairy, which is dramatically exaggerated when paired with Baby Bower's dungeons instead of dancing fairies. I think it also alludes to the fact that dungeons are full of tricks and traps, and Yoshi has to step pretty lightly to survive—like a sugar plum fairy :-D Don't get me wrong—I certainly don't think Totaka researched Late-Romantic Russian ballets for inspiration when writing for Yoshi's Story, but who knows, maybe he was looking at the beta images for the first Bowser dungeon and thought “You know what would be cute and ironic? Sugar Plum Fairy.” It's really quite hilarious to quote such a famous piece in a game that could not be farther from the story of The Nutcracker. Especially when Baby Bowser is anything but innocent. Again, we don't know that any of this was intentional--the only way to find out would be to ask Totaka himself LOL--but intentional or not, the song worked great, right? Because bottom line, this is Baby Bowser we're talking about here. King Bowser deserves epic, frightening music for his dungeons, but Baby Bowser is, in fact, a baby. It wouldn't make sense for him to have a choir, organ and drum corps accompanying his childlike dungeons. Thus, we have a little dose of celeste ;-) I think Baby Bowser's Lullaby was really a very clever way to convey that Baby Bowser is the bad guy, but reminding us that this game is about Yoshis and therefore will have cute music at all times--even if that cute music is occasionally slightly demented :-P On a final note: Igor Stravinsky actually was not the first to say "good composers steal." That famous quote is actually from T.S. Elliot, speaking about poetry ("Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal"). Stravinsky actually stole his own quote about stealing. OH THE IRONY!!! Enjoy this week's arrangements for Yoshi's Story's Baby Bowser's Lullaby, Love Is In the Air, Super Mario Kart's Star Power and Super Mario World 2's Flower Garden. More on the way! |

AuthorVideo game music was what got me composing as a kid, and I learned the basics of composition from transcribing my favorite VGM pieces. These are my thoughts and discoveries about various game compositions as I transcribe and study them. Feel free to comment with your own thoughts/ideas as well! Archives

July 2017

Categories

All

|

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed