|

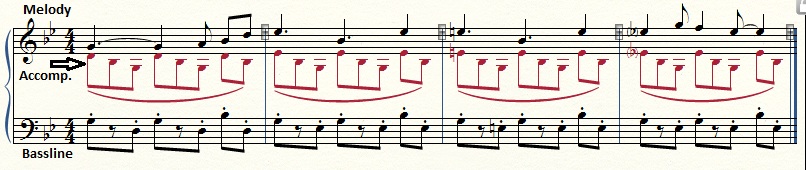

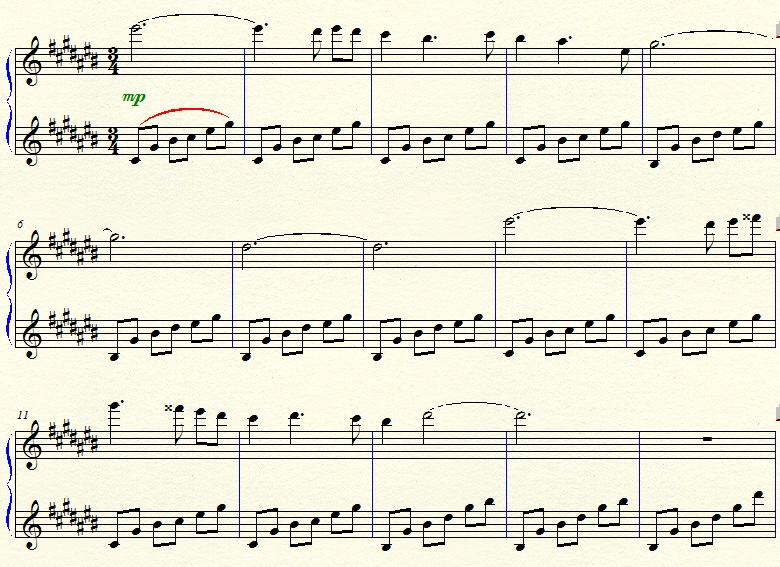

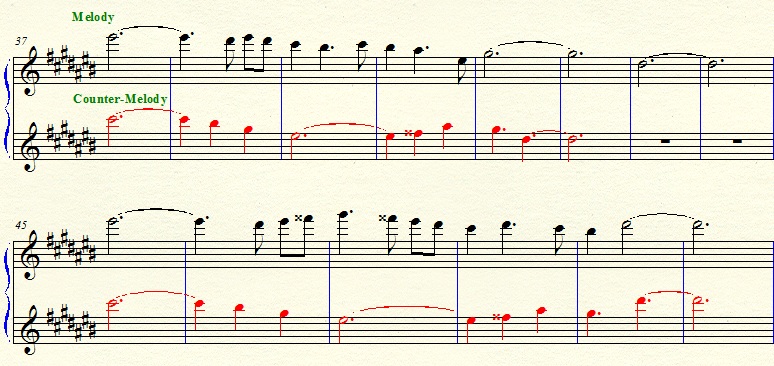

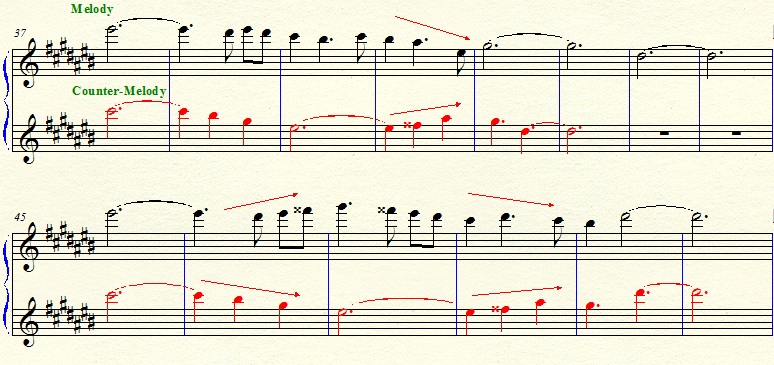

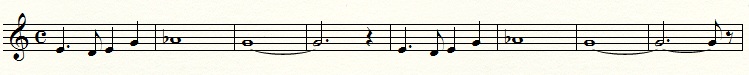

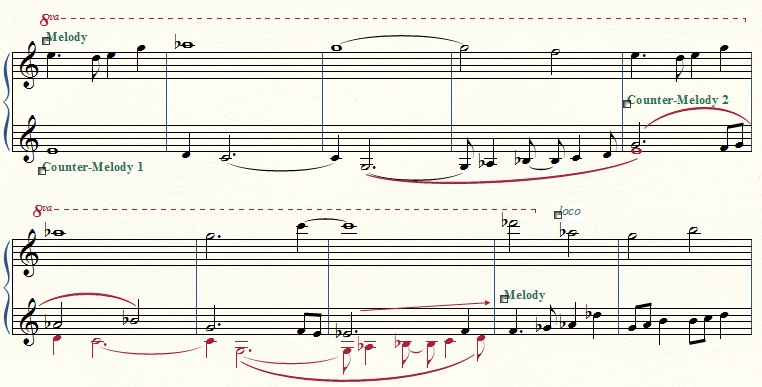

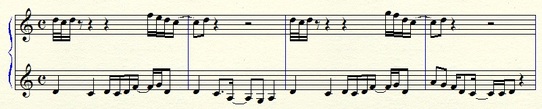

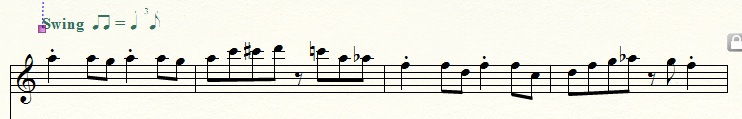

Let's change things up a little! Instead of talking about one game in particular this week, let's talk about a musical concept and how it is applied in games from different series. This is a big post I had a lot of fun writing about, because it's a really neat concept that can be really powerful when used correctly: the counter-melody. Wikipedia says the definition of counter-melody is “a sequence of notes, perceived as a melody, written to be simultaneously with a more prominent lead. Typically a counter-melody performs a subordinate role, and is heard in a texture consisting of a melody plus accompaniment.” What does all of that mean? Basically, a counter-melody is exactly what it sounds like: it's a secondary melody that is meant to “counter” the primary melody. It generally follows a totally different rhythm and contour (shape) than the primary melody, so that it stands out in the texture. A lot of the classic game tunes feature a “melody & accompaniment” form, like in Zelda II's “Palace Theme.” The middle line of music is obviously supporting the melody; it is not a melody in and of itself, but simply an accompanying pattern that lies underneath the melody. A counter-melody is different in that it would also have a melodic character of its own. The strength of using a counter-melody in video game music is that it adds variation to a repeated melody. Let's face it, most video game music HAS to be able to loop endlessly, right? A counter-melody is a great way to prevent the theme from getting old. A counter-melody can make the original melody sound way more interesting, by highlighting the differences between the two. Before we look at Banjo-Tooie's “Atlantis,” one of this week's new transcriptions, let's bounce back to a piece I posted a while ago, “The Bunnies” from Super Mario Galaxy. This is a freaking PERFECT EXAMPLE of how counter-melody works, and in a really lovely, mystical way. First, take a look at about half of the primary melody of The Bunnies. Check out the bottom staff in the piano; obviously just accompaniment, right? We wouldn't describe that figure as being melodic in nature—the repeated pattern is actually closer to an ostinato. Now let's jump ahead in the piece: Check out that second line. It's not simply arpeggiating chords, it has a distinctive shape and character of its own, completely unrelated to the primary melody. The primary melody is much more rhythmically active, on a punctuated harp string sound; the secondary melody has a fuller, sustained sound and less rhythmic activity. Each melody tends to move in opposition to the other; i.e., when one goes up, the other goes down. Now what does this mean musically? What does this convey to the listener? Here's my take on it, my own opinion: The primary melody kind of hops around innocently on that high harp sound, so for me, it represents the bunnies. The secondary melody sounds a bit softer to my ears, and is much more sustained and has a —for lack of a better word--”sci-fi” kind of synthy sound. This is just my own take, but it gives the piece a feeling of weightlessness for me (weightlessness...loss of gravity...HEY WAIT WE'RE IN SPACE). The sound design in and of itself suggests a feeling of wonderment to me, like a child exploring a new world. In the game, Mario has just woken up on a strange planet after being blown into space by Bowser; he wakes up and encounters space bunnies who encourage him to catch them. The purpose of this scene is to give the player more practice with Mario's game controls; so, not only does the music convey the dramatic content of the scene (“Where am I and who are these bunnies?”), it also reflects what is happening for the player him/herself: exploring the controls and the new space world you find yourself in. It's an innocent song, which conveys to the player that he/she can freely experiment with the controls without fear for Mario's life. It's pretty cool how much a simple counter-melody can add, isn't it? Let's look at some more examples. First, “Atlantis” from Banjo-Tooie. Primary melody: Now let's jump ahead to where the counter-melody comes in. Oooooh, something neat is going on here! The melody is obviously in the high flute, and in the lower flute at m. ___ we have what sounds to me like a long, sustained counter-melody. Then, at m. 39, ANOTHER counter-melody splits off of the first one. It only lasts for a few measures until m. 9 of this example, where it takes over the primary melody-line. Now the high flute has a supporting role, the low flute is the primary. It all happens in the span of just a few seconds and the result is seamless, each melody-line weaving in and out of the other (Like fish swimming in the ocean, OH SNAP!) One more example! This is from a personal favorite tune of mine, “Forest Frenzy” from Donkey Kong Country. Take a listen to the entire song here, see if you can pick out the counter-melody just by listening. Hopefully you caught it on that first hearing! Now check it out in the sheet music: Now, for me, the counter-melody does not stick out as strongly in this piece as in the other examples. This piece has a LOT of ostinati in it—those repeating rhythmic and chordal figures make up a lot of the catchiness of the song—but as a result of the repetitive nature of the texture, the counter-melody is kind of lost. It isn't as different from the melody as it could be. In fact, it's almost tempting to call it simply some sort of accompanimental figure—but the fact that it is a single-line melody (one note at a time) and it's in a higher register than the primary melody makes me think that this was intended to be a counter-melody. Not as prominent as the other examples we looked at...but maybe that was the point. This piece is highly rhythmic and the melody is not necessarily the most important feature. So the weaker counter-melody doesn't really take away from the piece, but helps the melody blend in with the rest of the texture.

That's a lot of information to digest, but hopefully you get the idea of all the different ways a counter-melody can function. To finish this ginormous post off, I want to quote a very famous poem by William Carlos William. “It is a principle of music / to repeat the theme. Repeat / and repeat again, / as the pace mounts.” This is more true than ever in video game music, a medium that requires musical looping for the player to have freedom to play at his/her own pace. It is how composers vary the theme, to make it different each time we hear it, that enables us as listeners to not become bored with the same thing over and over again. The video game world has a history steeped in extremely strong melodies—melodies so catchy that you can hear it literally a thousand times and not get bored—but as the hardware grew, so did the capabilities of the composers to create music with more variation. I mean, what was the average length of the typical video game song in the 80's, like one or two minutes? Now we have composers creating much longer pieces with more depth in the music that supports the melody; and that's how we get pieces with beautiful use of counter-melody like “The Bunnies,” “Atlantis” and countless other examples in video game music. Here are some more pieces of video game music with counter-melody...can you spot those moments just by listening? Can you find more examples in video game music that I haven't listed here? I'd love to hear them! New Super Mario Bros. Wii - Staff Roll Legend of Zelda: Windwaker - Staff Roll Ar-tonelico - Singing Hill Star Fox - Main Titles Enjoy this week's transcriptions of Atlantis and Grunty Industries from Banjo-Tooie! More on the way!

9 Comments

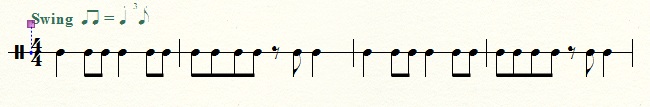

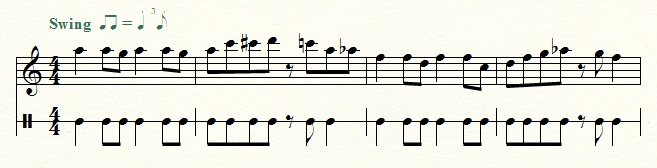

“Music theory” can be somewhat of a polarizing force in music school ;-) Some people love it, some people despise it with every fiber in their being. The reason for this is that music theory involves staring at scores for long hours and analyzing each and every note for connections to each and every other note in the score. It can quickly become visually and mentally exhausting. And most students have trouble with the “ear-training” aspect of it; there's sight-singing, where you have to sing a melody line that you've never seen before, on the spot, in front of your entire class. Or dictation, listening to a piece you've never heard before and having to write down the melody and bass line by ear. It's very challenging, and the fact that most public schools only offer music theory courses in high school doesn't help. Learning to read and comprehend music is like learning a whole separate language—it's harder to learn as an adult, rather than as a child. Me, I was lucky in school! I enjoyed the sight-singing, dictation and ear-training courses because it's something I had been doing ever since I was a child. I started transcribing video game music as hobby when I was just 10 years old, because I wanted to be able to listen to the music without having to play the games. So when I started my first music theory courses in high school, I was surprised to discover that my ear-training was already very strong, at a more advanced level than most of my class. But even with that solid foundation, score analysis still would have my head aching and my eyes rolling after about half an hour. It's true that composers write with a form in mind--they create melodies and themes that work well together, have them connect in some way, use certain distinct elements to build the fabric of a piece, etc. So, it's always, always worth it to look at a score and discover the individual elements that make up the music; it's like looking at the blueprints of a machine and figuring out how all the parts work together; with that knowledge, you can start building your own machines! But the flipside is that you have to be careful that theorizing doesn't completely take over—all of a sudden, you find “things” in the music--motives, phrases, rhythms, intervals--that seem meaningful at first, but were quite possibly accidental, unintentional and had no bearing on how the piece was written. The fact that it's called music theory means you can basically draw any conclusions you want, but I think sometimes a composer chooses the notes not because of some mathematical equation, not because he had used a similar pattern upside down and backwards 400 measures earlier, not because the notes are actually code for the initials of his first girlfriend—he chooses them because he likes the way they sound. It's just plain aesthetic taste. There's also a great deal of intuition involved in composing—putting different elements together because it "feels right," without coming up with some musical formula to support it. Now that we've discussed the ups and downs of music theory :-P let's do a little theorizing! Today we're looking at Donkey Kong Country 2: Diddy's Kong Quest. The DKC soundtracks are some of my favorite of all time, especially DKC2. I have played this game more than any other game I've had in my possession, even more than Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time and Super Mario World. Words cannot convey how much I adore this game. In 2010, I was asked to promote our Indianapolis VGL show by performing some video game tunes at our ticket booth inside Gen Con. I tried to pick songs from all the big franchises that worked well as flute solos, but Donkey Kong proved pretty tricky. To me, the magic of the music came not just from the catchy melodies, but from the colors and orchestration. I use the term orchestration loosely; obviously, the music of the Donkey Kong games did not use a traditional symphony orchestra, but in this case, “orchestration” refers to the specific sounds and timbres that Wise used to produce the melody, harmony, bassline, textures, rhythms, etc. So there I was, listening to various DKC themes. I finally picked out “Snakey Chanty,” which had a fun, fast melody, and while I was transcribing it, I got some major deja vu. Something about the song seemed really familiar, like I had heard it somewhere else. I mean, I knew it was drawn from DKC's Gangplank Galleon with a jazzy twist, but there was something else about it that I just couldn't place. It was killing me—what was it about this song that sounded so familiar? Then it clicked. Take a listen to a bit of “Island Swing” (Jungle Hijinx) for a moment. Check out the rhythmic pattern in the drums, one of the most iconic game themes of all time: Now check out a bit of the melody-line of Snakey Chanty: Notice anything about the rhythm of each song? THEY'RE THE SAME.

I wanted to punch myself in the eyeball for not noticing the connection right away—the super catchy “Snakey Chanty” from DKC2 is based off of the rhythm of “DK Island Swing” from the previous game! With only slight differences, the rhythm has been transplanted into a totally new setting; originally an earthy jungle beat, it's now a breezy, almost Dixieland Jazz type melody. Wise rehashed an old theme into something brand new, but still totally recognizable. SO! Why did I write all of that stuff about music theory in the beginning of this article? Because I want to make it perfectly clear that is just my theory. Yes, Snakey Chanty and DK Island Swing share the same rhythm, that is a fact. But whether this connection was intentional or completely intuitive on the part of the composer...that's something we'd have to ask David Wise himself ;-) But whether it was intentional or not, I think it was a really ingenious way to musically connect two games in a series, without simply copying the same exact track from one game to the other. NO WONDER HIS NAME IS DAVID WISE. HA-HA SEE WHAT I DID THERE. Enjoy this week's transcriptions of Bayou Boogie, Snakey Chanty and Swanky's Swing from Donkey Kong Country 2: Diddy's Kong Quest! More on the way! |

AuthorVideo game music was what got me composing as a kid, and I learned the basics of composition from transcribing my favorite VGM pieces. These are my thoughts and discoveries about various game compositions as I transcribe and study them. Feel free to comment with your own thoughts/ideas as well! Archives

July 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed